Longhouses were the typical dwelling unit of the Haudenosaunee People, from Ontario through New York State. They usually housed a number of families within the same clan. A large village might contain as many as 120 longhouses. The average multiple-family dwelling was approximately 60 feet long, 18 feet wide, and 18 feet high. Many larger houses existed, however, especially in the more populous villages. The largest longhouse yet discovered was located in a community in Onondaga County and measured 334 feet long by 23 feet wide.

The houses consisted of a row of forked poles fastened into the ground about four or five feet apart. Cross poles were then secured to the forked tops of the uprights so as to form an arching roof. Rafters were affixed to the roof frame, and large sheets of bark, which had been stripped from the trees in the spring when the sap was flowing, were tied upon the frames, rough side out. An outer set of poles along the roof and sides of the house held the bark firmly in place. There were smoke holes in the roof at regular intervals, usually twenty feet apart. These were covered with a moveable piece of bark which could be opened or closed with a pole from below. The hearth on the ground below each smoke hole was shared by two families.

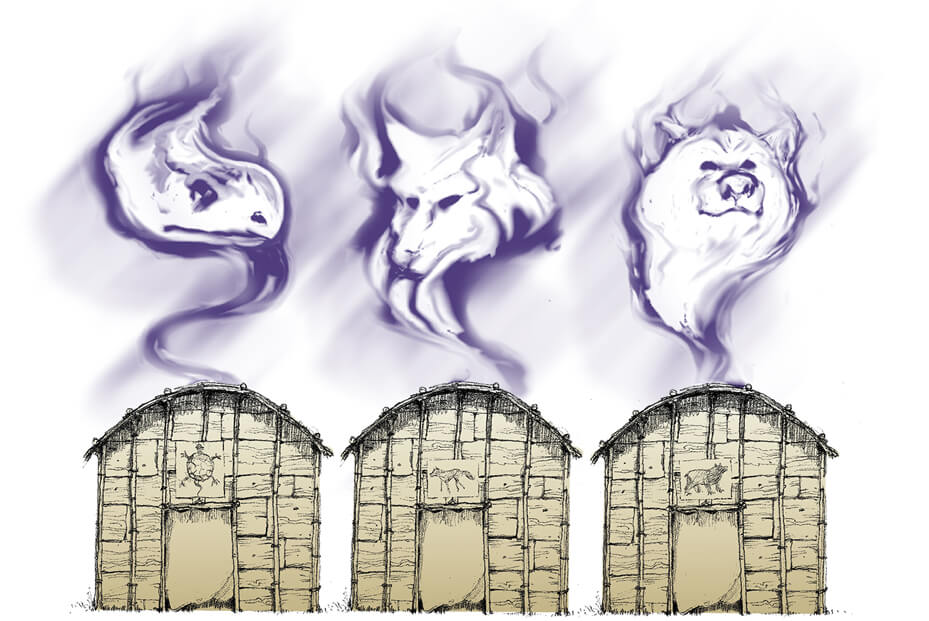

At each end of the house there was a door made either of animal hide or of hinged bark which could be lifted up. Bunks along the inside wall served as beds at night and benches during the day. Overhead shelves were used for storage. Braided strings of com, dried fish, and other dried foods also hung on poles overhead. The house within was divided into a series of compartments to accommodate each family. Storage space was found in comers and in closets separating the compartments. The front of the house, over the door, was frequently adorned with carved or painted likenesses of the clan symbols of the families living within.

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, the Haudenosaunee began to build the same type of log houses used by the white frontier settlers. Bark houses survived to some extent well into the middle of the nineteenth century but gradually gave way to the sturdier log and frame dwellings.

Condensed from the book, ‘The Iroquois in the American Revolution’ by Barbara Graymont