During the Revolutionary War, Oneidas bound themselves “to hold the Covenant Chain with the United States, and with them to be buried in the same, or to enjoy the fruits of victory and peace” (Duane, 1778). Choosing to ally with the young United States, the Oneida Indian Nation served the American cause with fidelity, effectiveness, and at terrible cost.

As the Oneidas expressed it: “In the late war with the people on the other side of the great water and at a period when thick darkness overspread this country, your brothers the Oneidas stepped forth, and uninvited took up the hatchet in your defense. We fought by your side, our blood flowed together, and the bones of our warriors mingled with yours” (Hough 1861 1:124).

The war forced people to make life-and-death decisions carrying frightful risks for their loved ones. Many faced such personal consequences at the Battle of Oriskany on August 6, 1777 — a bloody fight dividing neighbors, families, and even nations in the Mohawk Valley.

This article examines the personal face of war for the Haudenosaunee by focusing on two native leaders: Hanyery (or Han Yerry) of the pro-American Oneidas whose territory bordered the limits of white settlement, and Joseph Brant of the pro-British Mohawks living in the Mohawk Valley. They opposed each other long before the Revolution. Each man brought his nation into the shooting war at Oriskany and each personified his nation’s involvement in the war. Their meeting at Oriskany started a chain of events affecting the history of three nations: Oneida, Mohawk, United States.

The Mohawk Valley Before the War : The Klock Dispute

In the early 1760s, Hanyery and Brant came into conflict on opposite sides of the longest running, most bitter land dispute of the upper Mohawk Valley. The positions taken by Hanyery and Brant in the Klock dispute foreshadowed the sides they would choose at Oriskany years later.

George Klock, a prosperous German farmer living across the Mohawk River from the Mohawk upper settlement, Canajoharie, obtained a controversial patent on land that included the Mohawk settlement. This dispute pitted Sir William Johnson and Canajoharie Mohawks against Klock and “Klock’s Indians,” who included Oneidas.

Simmering over at least fourteen years, the argument sometimes was fought in the courts and sometimes with fists. Sir William regarded Klock as one of the greatest rogues of the continent but never succeeded in annulling Klock’s claim (Sir William died with the unresolved problem of Klock on his lips in 1774).

In 1763, some Mohawks of Canajoharie complained of being threatened by Oneida “han Juery” (WJ 4:165; Druke 1981:228). Shortly after, a Klock-related survey was disrupted by twenty-year-old Joseph Brant (WJ 4:233).

Why Hanyery stood with Klock is not known. Perhaps he contested a Mohawk claim to what Oneidas regarded as Oneida land (end note 2).

Hanyery apparently moved away from the dispute to found the village of Oriska by 1765 with other Oneidas and some Mohawks from Canajoharie (Love 1899:68; Mereness 1916:418).

Joseph Brant, increasingly prominent in the British Indian service, continued to contest Klock’s claim. Brant took his complaint to the Royal Governor of New York in 1772 then, in 1776, to the colonial secretary in London (Kelsay 1984:123,166).

Taking Sides in the Mohawk Valley

Long before the war, people in the Mohawk Valley began sorting themselves out as for or against British rule as embodied by Sir William Johnson (Becker 1909:171,202; Countryman 1989:127-28; Venables 1967:93,153). Many ordinary citizens of the valley resented the wealth and power of Sir William. He controlled the land west of Albany by virtue of his government position (Indian Superintendent). He planned and built the country of Tryon County, then named it for himself (Johnstown). He owned the county jail, courthouse, and Anglican church. In local elections, Sir William determined both the candidates and the voters (Venables 1967:63-64; Guzzardo 1976a). Since Sir William was the colony’s biggest land owner, anyone hoping to get rich through land speculation in Indian land had to enjoy his favor (Guzzardo 1976b:265).

Iroquois people viewed Sir William favorably if, like the Mohawks of Canajoharie, they enjoyed his personal patronage. Others living farther away were impressed by Sir William’s promise, on behalf of the British Empire, to safeguard Indian land from the depredations of American frontier settlers and squatters. Oneidas, however, had reason to be skeptical of such promises. Most land they lost went not to individual settlers but to Sir William himself in quasi-legal transactions. For example, in the 1768 Fort Stanwix Treaty, intended to establish a permanent line (Line of Property) between Indian and non-native territories, the Oneidas gave up a vast acreage that became the property of Sir William and other land speculators.

In wider context, the 1763 disagreement between Hanyery and Brant suggests they held different opinions about how Sir William wielded power and, perhaps, about rightful land ownership. Their positions in the Klock dispute would lead them in opposite directions as war approached.

War Comes to Oneida Country : The British Campaign of 1777

In 1777, the British thought they could win the war by isolating New England, the hotbed of the American rebellion, from the other American colonies. Their plan called for several armies to meet in the region of Albany:

- a large invasion force under Burgoyne would proceed south from Canada across Lakes George and Champlain; 2. a second force under St. Leger would secure Fort Stanwix and the Mohawk Valley; 3. Howe’s army in New York would, it was hoped, move up the Hudson Valley to join the other forces.

An Incident Outside Fort Stanwix

As British forces approached Fort Stanwix, an extraordinary meeting occurred between Paulus, probably a teenage boy of Oriska, and Joseph Brant (Draper 11:204B-205). The substance of their conversation (sometime about August 2) was long remembered in Oneida tradition:

“Some Oneidas were inside the fort; the others outside as pickets and spies. When [Paulus] was alone & in the woods some miles in advance of the fort, he discovered the enemy approaching in the distance– & they discovered him at the same time.

Brant hailed him– begged him to stop as he was in the act retreating, pledging his honor that he should neither be hurt nor detained. So Paulus raised his gun & invited Brant to approach alone for an interview– as they then would be on an equality. But he ordered Brant as he neared him to halt a few steps off– still presenting his gun, with his finger on the trigger– and bade Brant deliver whatever message he had to offer.

Brant insinuatingly offered him a large reward & aplenty as long as he should live, if he would only join the King’s side & induce other Oneidas to do so, & help the British to take Fort Stanwix. Paulus firmly rejected any such blandishments, saying he and his brother Oneidas had joined their fortunes with those of the Americans, & would share with them whatever good or ill might come. Brant portrayed the great & resistless power of the King, and professed to deplore the ruin of the Oneidas if they should foolishly and recklessly persist in their determination. Paulus replied that he & the Oneidas would persevere, if need be, till all were annihilated; and that was all he had to say when each retired his own way.

As Paulus hastened to the fort & reached his fellow Oneida pickets, the enemy had run with equal speed, and had commenced firing on the opposite side of the fort while Paulus and his companions were entering on the other– & had even to fight their in. The British then began to dig to undermine the fort, to blow it up. Oneidas used to say, if they had not been there to aid in its defense, the fort might not have been saved (Draper 11:202-4).”

The Battle of Oriskany

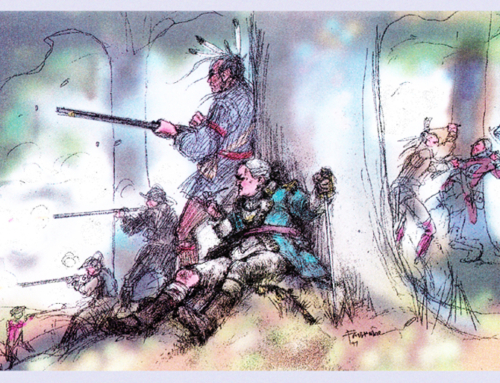

Learning of St. Leger’s invasion, American volunteers of the Mohawk Valley (Tryon County Militia) rushed west to relieve their besieged comrades at Fort Stanwix. On August 6, 1777, they blundered into an ambush set by the British around a small ravine two miles from Oriska. A tremendous slaughter of Americans occurred during the opening minutes of the engagement. The survivors gathered around their commander, Nicholas Herkimer, on a plateau west of the ambush ravine. They and their Oneida allies fought the British and Tory Indians to a standstill in the ensuing battle.

Joseph Brant at Oriskany

August 5, 1777: British forces besieging Fort Stanwix are able to set an ambush for the approaching militia because they receive timely warning of the American advance from Molly Brant.

The fifth, in the afternoon, accounts were brought by Indians, sent by Joseph’s sister from Canajoharie, that a body of rebels were on their march and would be within ten or twelve miles of our camp by night. A detachment of four hundred Indians was ordered to reconnoiter the enemy. — (British expedition member Daniel Claus, 16 October, 1777) [DRCHNY 8:721]

Thirty-four-year-old Joseph Brant was at the battle, but the precise role he played is unknown. At the time, no one claimed Brant was in an important position of command or that he chose the site of the ambush. According to an elderly Seneca veteran of the battle interviewed in 1850, Brant “had about 50 or 60 Mohawks in this battle” (Draper 4:24-25).

Apparently Brant was in the ambush circle near where the road crossed the creek: Mr. Brant signalised himself highly by advancing in the Rebels rear, it harassing their retreat and making great slaughter chiefly with spears and lances. — (Claus’ Anecdotes of Brant, 1778) [Penrose 1981:321]

According to American traveler Samuel Woodruff in 1797, Brant’s recollection of the battle was that:

he and his Mohawks were compelled to flee in a dispersed condition through the woods, all suffering from fatigue and hunger before they arrived at a place of safety. Their retreat began at nightfall. They were pursued by a body of Oneidas, who fought with General Herkimer. The night was dark and lowery. Exhausted by the labors of the day, and fearful he might be overtaken by the pursuing Oneidas, Brant ascended a branching tree, and planting himself in the crotch of it, waited somewhat impatiently for daylight (quoted in Stone 1851 1:244).

Hanyery at Oriskany

Hanyery led the Oneidas of Oriska and possibly other villages into battle as a chief warrior. Probably in his fifties, he was “too old for the service, yet used to go fearlessly into the fights,” an Oneida later recalled (Draper 11:210). Hanyery and other Oneidas apparently fought on the main plateau of the battlefield. Hanyery’s widow, Tyonajanegen, reported her husband lost two blankets in the battle (Pickering 62:160). This suggests Hanyery stripped off his outer clothing to fight “Indian style.”

Oneidas interviewed in 1877 remembered the tradition that Hanyery and other Oneidas – a good many, said one; perhaps a hundred, said another – were in the Oriskany battle (Draper 11:194).

According to an account originating from Tyanajanegen:

Hon Yerry was shot through the right wrist so as to disable him from loading his gun (he on horseback), when his wife repeatedly loaded it for him, & he managed to aim its contents at the enemy. He had a sword hanging by his side, indicative of his rank as a captain or war leader. His wife had a gun also and used it too in the fight. So she related, and added that there was a good deal of close intermixing between Americans and British, and American and British Indians, & she could see the British all around (Draper 11:196-97).

Much of this story was confirmed in a contemporaneous newspaper description:

a friendly Indian, with his wife and son, who distinguished themselves remarkably on the occasion. The Indian killed nine of the enemy, when having receiving a ball through his wrist that disabled him from using his gun, he then fought with his tomahawk. His son killed two, and his wife on horseback, fought by his side, with pistols during the whole action, which lasted six hours (Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser, 3 September 1777, p. 2).

After the Battle: The Oneida Contribution to Victory

Having played a key role in repulsing St. Leger’s western army, Oneidas rushed east to Saratoga where they served with distinction in the campaign ending in another British defeat. American victories in 1777 prompted France and other European nations to join the war against Great Britain. For England, now embroiled in a world war against European rivals, the revolt of the American colonies became a sideshow. France’s aid proved to be decisive in the winning of American independence.

The events of 1777, therefore, were crucial to the outcome of the Revolutionary War. In that year of destiny, the Oneida Indian Nation contributed more to the birth of the United States than any other community of comparable size in the colonies. The biggest winner in Oneida involvement led by Hanyery was the United States.

Vengeance

No one knows whether Hanyery and Brant met at Oriskany. A series of retaliatory measures after the battle suggests each one sought revenge against the other.

- Tory Iroquois destroyed Oriska because Hanyery and his people helped the Americans at the battle.

The Oneidas of Oriska about fifty in number, including women and children, had all their habitations stock and provisions destroyed by the enemy because they had joined General Herkimer. — (American Philip Schuyler, 15 March 1778)[Penrose 1981:119-20]

The Indian action near Fort Stanwix happening near a settlement of Oneida Indians in the rebels interest, who were at the same time in arms against our part; the Six Nation Indians, after the action, burnt their houses, destroyed their fields, crops, &c. Killed and carried away their Cattle. — (British Daniel Claus, 6 November 1777) [DRCHSNY 8:725]

- Then Hanyery seized property from Molly Brant, Joseph’s sister who had warned of the approaching Americans: the rebel Oneidas, after our retreat, revenged upon Joseph’s sister and her family (living in the Upper Mohawk town) on Joseph’s account; robbing them of cash, clothes, cattle &c and driving them from their home. — (Daniel Claus, 6 November 1777[ibid.]

Molly fled but there is no evidence Oneidas drove her from her home or threatened her. However, Oriska Oneidas did join with other Mohawk Valley residents to loot the homes of Tories (including Mohawks) around Canajoharie. “At the head of these affairs” was Peter Dygart, chairman of the German Flats (district) Committee of Safety (Penrose 1981:134). According to Honyery “and other Oriska Indians,” Dygert told them, “Where we lost one cow, ox, horse, hog, sheep &c. that we should take two in lieu thereof.” Dygart and Hanyery were supposed to have divided a number of goods taken from Molly Brant’s (ibid.:130-34).

Hanyery, it was said, moved into Molly Brant’s house (Graymont 1972:147; Kelsay 1984:209). The otherwise homeless Oriska Oneidas apparently lived in Mohawk houses at Canajoharie throughout the rest of the war (Hammond 1939 3:133; Kelsay 1984:335).

- Brant lashed out at the Oneidas whenever he could. — In early 1780, Brant captured two elderly Oneidas, Skenandoa and Good Peter, who were on a peaceful mission. After harsh confinement, Brant required them to accompany Tory raiding parties on the Oneidas and patriot residents of the Mohawk Valley (Kelsay 1984:284; Draper 11:205-7,240-41). — Brant led a war party which destroyed the main Oneida village — Kanonwalohale, present Oneida Castle — in July 1780 (ibid.:293): The last [war party] sent out under Joseph Brant consisted of about 300 and was certainly the means of reducing some part of the Oneida [Indian] nation to obedience, which was at last effected by coercion…Joseph burned their principal village and a stockaded fort made by the rebels for their protection. — (Frederick Haldimand, Governor General of Canada, 25 October 1780) [Davies 18:208] — Brant wanted to attack Oneida refugees in the Mohawk Valley in 1781. In 1782, he planned to revenge himself on Oneidas living at Canajoharie (Kelsay 1984:293,306).

Hanyery received a commission as captain in the American army in 1779 (Penrose 1981:99). His exploits during the remainder of the war are undocumented.

The Property Losses of Hanyery and Brant

Brant was the richer man (372 v. 287 pounds in claimed personal property). Brant said that he owned 592 acres. Hanyery was not listed as private owner of any land because Oneida land was property held in common by the Oneida Indian Nation.

The British government reimbursed Brant for all of his claimed losses — promptly and completely (Kelsay 1984:390-91).

The American government never compensated Hanyery. Finally, in 1795, the U.S. reimbursed Hanyery’s widow less than half the amount claimed lost (120 pounds). Excusing themselves for awarding Hanyery so little, the Americans noted that he was already “greatly reimbursed by the Mohawk’s property” — presumably meaning Molly Brant’s possessions.

Brant lost his Mohawk Valley homeland. The Crown, however, awarded Brant and his followers an estimated one million acres on the Grand River in Ontario (Kelsay 1984:371). Now known as the Six Nations Reserve, the tract still inhabited by the descendants of the Tory Iroquois who relocated there with Brant after the war.

Brant won great renown during the war, becoming probably the best known American native person in the world. Though often the center of controversy, he enjoyed considerable prestige and civil power on the reserve.

Hanyery won little fame for his part in the war. In 1784, New York State confiscated Hanyery’s village of Oriska by legislative act (end note 3). But “these poor people of Orisca fought with you,” an incredulous Oneida protested to New York’s governor in 1788 (Hough 1861 1:238).

Hanyery was always proud of the heroic services he rendered to his American allies. His last recorded act was to request American uniforms for himself and his sons as they undertook a mission to the West on behalf of the U.S. (O’Reilly Papers 9: Israel Chapin to Timothy Pickering, June 1793).

About Hanyery

Oneida chief warrior of the Wolf clan: born about 1720, died before November 1794. Hanyery was born in the Mohawk Valley, his father said to be a Palatine German (Draper 11:194,211). Hanyery was remembered years later as quite a gentleman in his demeanor (ibid.:191)(end note 1).

See also: The Museum of the American Revolution

He first appears in the documentary record as Han Ury, alias Tewahowagarahe, a warrior serving with British forces in the Niagara campaign of the French and Indian War in 1759 (WJ 13:176).

Hanyery’s Indian name, Tehawenkaragwen, meant “he who takes up the snowshoe” (Draper 11:200). Curiously, this looks very similar to the name of Joseph Brant’s father: Tehowaghwengaraghkwin (Kelsay 1984:39). Were Hanyery and Joseph Brant closely related?

About Brant

A Mohawk of the Wolf clan (1743-1807), his Indian name was Thayendanegea, “two sticks of wood bound together,” Mohawk of the Wolf clan (Kelsay 1984:43). His older sister, Molly, was the common-law wife of Sir William Johnson, Royal Indian Superintendent of the Northern Department. This family connection afforded Joseph opportunities for education and advancement in the British Indian service before the war.

Brant’s ties to the British cause, through his sister and his patron Sir William, were strong. But his family connections to the Oneidas were also close. His first wife, Neggen Aoghyatonghsera (Peggie), was an Oneida (married 1765 and died 1771)(ibid.:99-100,133). Brant accidentally killed his Oneida son by that marriage in 1795 (ibid.:564,754). A second wife, Peggie’s half-sister Susannah, probably was Oneida also. Married about 1773, Susannah is said to have died shortly after (Kelsay 1984:134,671-72 at note 52). According to Oneida tradition, Joseph had a third Oneida wife (Margaret, daughter of Skenandoah) sometime during the war (Draper 11:193-94,243).

End Notes

- Hanyery may be one form of the German/Dutch patois of the Mohawk Valley for “John George” in English (the nickname for “George” apparently being “Ury” in German and “Yeary” in Dutch). In support of this interpretation is the fact that Hanyery was referred to as “Indian George” and “Capt. George” (Elmer 1848 3[1]:24; Hough 1861 1:40).

His name was also written in English as Hans Jurie and John Jury (Special Committee Report 1889:222; Hough 1861 2:348). For a time in the late 1780s, Hanyery was called “Ojistalale” or Grasshopper, a name he bore in his role as counselor to a young sachem of the Wolf clan (Hough 1861 1:222).

Hanyery has often been called “Doxstader” but he never signed documents that way and the name was not applied to him during his lifetime. The surname Doxstader, possibly derived from a baptismal sponsor (Faux 1987:32,35), was taken up by his children and apparently applied to Hanyery retrospectively.

- There are vague but persistent indications of Oneida presence and proprietary interest to this area. For example, Dean Snow suggests an Oneida village existed near the upper Mohawk village from about 1615 to 1635 (1995 1:294-97). The first Palatine Germans in the Mohawk purchased land in the same area from “Caquayadighe,” a person Paul Wallace tentatively identified as “Aquoyiota” (variously rendered), an Oneida known to Conrad Weiser and Sir William Johnson (1945:34,162).

- Oriska was located in the problematic Oriskany Patent of 1705, issued to five prominent men of the New York colonial government including influential Peter Schuyler of Albany. Far west of any other grant for many years, the patent specified a ridiculous quitrent of ten shillings and contained no clause requiring the patentees to settle or improve the land. In 1756, the Lords of Trade recommended to New York Governor Hardy “that he present the facts to the Council and Assembly with a view to securing a law vacating such patents as the…Oriskany because their fraudulent grants were one of the principal causes of the decline of the English interests with the Indians. Governor Hardy did not attempt to obtain this legislation” (Higgins 1976:84).

One reason Sir William insisted the Line of Property (1768) had to begin west of present Rome was to comprehend (and thus retain) the Oriskany Patent within English territory. Even though title to the Oriskany Patent was questionable, it continued intact as a legal fiction from British into U.S. jurisdictions. In 1784, New York State empowered itself to assume ownership of the Oriskany Patent as an act of confiscating Tory property (Penrose 1985:77).

References Cited

Becker, Carl Lotus 1909 The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York, 1760-1776. University of Wisconsin Bulletin 286, Madison.

Campbell, William W. 1831 Annals of Tryon County; Or, The Border Warfare of New-York during the Revolution. New York: J & J Harper.

Countryman, Edward 1989 [1981] A People in Revolution: The American Revolution and Political Society in New York, 1760-1790. New York: W.W. Norton.

Davies, K.G., ed. Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783: Colonial Office Series (20 volumes, 1972-1979). Dublin: Irish University Press.

Draper Lyman C. Draper Manuscripts, Series U (Frontier War Papers), Vol. 11 and Series S (Draper’s Notes), Vol. 4. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

DRCHNY Documents Relative to the Colonial History of New-York (15 volumes, 1853-1887). E.B. O’Callaghan and B. Fernow, eds. Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company.

Druke, Mary A. 1981 Structure and Meanings of Leadership among the Mohawk and Oneida during the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Ph.D dissertation, University of Chicago.

Duane James Duane to George Clinton, 3 March 1778. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Washington, D.C.

Elmer, Ebenezer 1848 Journal of Lieutenant Ebenezer Elmer. New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings III(1): begins at page 21.

Faux, David K. 1987 Iroquoian Occupation of the Mohawk Valley During and After the Revolution. Man in the Northeast 34:27-39.

Graymont, Barbara 1972 The Iroquois in the American Revolution. Syracuse University Press.

Guldenzopf, David B. 1986 The Colonial Transformation of Mohawk Iroquois Society. Ph.D dissertation, State University of New York at Albany.

Guzzardo, John C. 1976a Democracy along the Mohawk: An Election Return, 1773. New York History 57:30-52. 1976b The Superintendent and the Ministers: The Battle for Oneida Allegiances, 1761-75. New York History 57:254-83.

Hammond, Otis G., ed. 1939 Letters and Papers of Major Gen. John Sullivan, Continental Army (3 volumes). Concord: New Hampshire Historical Society.

Higgins, Ruth L. 1976 [1931] Expansion in New York. Philadelphia: Porcupine Press.

Hough, Franklin B. 1861 Proceedings of the Commissioners of Indian Affairs, Appointed by Law for the Extinguishment of Indian Titles in the State of New York (2 volumes). Franklin B. Hough, ed. Albany: Munsell.

Kelsay, Isabel Thompson 1984 Joseph Brant, 1743-1807: Man of Two Worlds. Syracuse University Press.

Lossing, Benson J.| 1859 The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution (2 volumes). New York: Harper & Brothers

Love, W. DeLoss 1899 Samson Occom and the Christian Indians of New England. Boston: Pilgrim Press.

Mereness, Newton D., ed. 1916 Travels in the American Colonies. New York: Macmillan.

New York State Archives Oriskany Patent, 1785 and Fort Stanwix, 1791. Maps 54 and 384, Surveyor General Series (AO273), Albany.

O’Reilly Papers Papers Relating to the Six Nations: Selections from Volumes 6-15. Documents on microfilm compiled by the New-York Historical Society from the O’Reilly Collection (Indians of Western New York), New-York Historical Society. New York.

Penrose, Maryly B., ed. 1981 Indian Affairs Papers: American Revolution. Franklin Park, NJ: Liberty Bell. 1985 Mohawk Valley Land Records: Abstracts, 1738-1788. Franklin Park, NJ: Liberty Bell.

Pickering Timothy Pickering Papers, 1758-1829. Vol. 62, Letters and Papers of Pickering’s Missions to the Indians, 1792-1797. Massachusetts Historical Society Microfilm Publication 2 (1966). Boston.

Snow, Dean R. 1995 Mohawk Valley Archaeology (2 volumes). Institute for Archaeological Studies, University at Albany, State University of New York.

Special Committee Report 1889 Report of the Special Committee to Investigate the Indian Problem of the State of New York, Appointed by the Assembly of 1888. Albany: Troy Press.

Stone, William L. 1851 [1838] Life of Joseph Brant — Thayendanegea: Including The Border Wars of the American Revolution (2 volumes). Buffalo: Phinney.

Venables, Robert William 1967 Tryon County, 1775-1783: A Frontier in Revolution. Ph.D dissertation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Wallace, Paul A.W. 1945 Conrad Weiser, 1696-1760: Friend of Colonist and Mohawk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

WJ The Papers of Sir William Johnson (14 volumes, 1921-1965). J. Sullivan et al., eds. Albany: University of the State of New York.