THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR, ONEIDA’S LEGACY TO FREEDOM

The Oneida Indian Nation played a significant role in the Revolutionary War, siding with the Americans against the British. Having fought valiantly in several key battles of the American War for Independence including the battles of Oriskany, Saratoga and Barren Hill, the Oneida Indian Nation became known as the United State’s first allies.

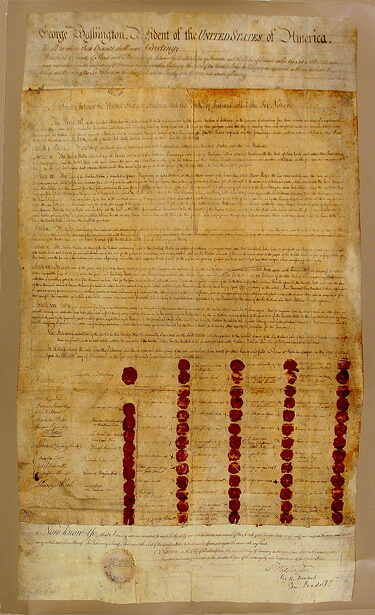

The Oneida Indian Nation’s loyalty, courage and sacrifice was formally recognized by the U.S. Congress in 1794 with the Treaty of Canandaigua, a document signed by President George Washington that affirmed the Oneida Indian Nation’s right to oversee its affairs and lands without interference from other governments.

Treaty of Canandaigua

The Treaty of Canandaigua is the oldest treaty still recognized by the federal government. Each year, the U.S. Department of Interior recognizes the treaty by giving annuity cloth to the people of the Oneida Indian Nation.

The original treaty signed by President Washington is housed at the National Archives in Washington, DC. This document between the United States and the American Indian nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois) was signed on Nov. 11, 1794. Known as The Treaty of Canandaigua or Pickering Treaty, it was ratified on January 21, 1795 and signed by President George Washington. According to the U.S. Constitution, once approved, treaties “shall be the supreme Law of the land…”

One of the paramount issues addressed by the treaty was that the United States acknowledged the lands reserved to the Oneidas and others in the confederacy. Within the lines of this paramount treaty the United States and Oneida Indian Nation agree to their boundaries and commit never to interfere with each other’s land:

“The United States acknowledges the lands reserved to the Oneida… to be their property; and the United States will never claim the same, nor their Indian friends residing thereon and united with them, in the free use and enjoyment thereof …”

In December, 1777, the Continental Congress gratefully addressed the Oneidas in these terms:

Hearken to what we have to say to you in particular: It rejoices our hearts, that we have no reason to reproach you in common with the rest of the Six Nations. We have experienced your love, strong as the oak, and your fidelity, unchangeable as truth. You have kept fast hold of the ancient covenant-chain, and preserved it free from rust and decay, and bright as silver. Like brave men, for glory you despised danger; you stood forth, in the cause of your friends, and ventured your lives in our battles. While the sun and moon continue to give light to the world, we shall love and respect you. As our trusted friends, we shall protect you; and shall at all times consider your welfare as our own. Journals of the Continental Congress 9:996 The State of New York expressed its appreciation of the Oneidas on September 3 of the same year: “Resolved, that the Oneida [Indian] Nation are the allies of this State and that we shall consider any attack upon them as an attack upon our own People.” Public Papers of Governor George Clinton 2:272

At Oriskany

Reporting on the Aug. 6, 1777 Battle of Oriskany – where at least 60 Oneidas fought with the colonists — the newspaper Pennsylvania Journal & Weekly Advertiser of Sept 3, 1777 described Oneida Han Yerry and his family as…

“… a friendly Indian, with his wife and son, who distinguished themselves remarkably on that occasion. The Indian killed nine of the enemy, when, having received a ball through his wrist that disabled him from using his gun, fought with his tomahawk. His son killed two and his wife, on horseback, fought by his side with pistols during the whole action.”

Han Yerry’s wife, Tyonajanegen aided her husband on the field of battle by loading his gun for him. For six hours, the duration of the fight, she fought side by side with her husband.

Tyonajanegen then went forth and notified the other colonists of the great bloodshed that had ensued from the British ambush of the colonists at Oriskany.

At Saratoga

“In the 1777 campaign, the Oneidas were instrumental,” said Larry Arnold, chairman of the Friends of Saratoga Battlefield. “They were the first sovereign nation to recognize the country of the United States. People don’t realize the staggering losses the Oneidas sustained during the Revolutionary War.”

Allies in War, Partners in Peace

Visitors to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. are encouraged to begin their tour on the fourth floor, the level named for the Oneida Indian Nation. Featured on this top floor is a pause area and in its confines is the statue “Allies in War, Partners in Peace,” a bronzed embodiment of the friendship that was forged between the Oneida Indian Nation and the United States during the Revolutionary War.

Veterans Treaty

Unlike the Treaty of Canandaigua, the Veterans Treaty signed Dec. 2, 1794 in Oneida Castle was specific to the Oneidas. The document was an agreement to indemnify Oneidas and Tuscaroras for losses and services in the Revolutionary War. This treaty is remarkable because it is the only one in which the United States commemorates victory jointly achieved with an Indian ally.

The first lines of the treaty read: “Whereas, in the late war between Great Britain and the United States of America, a body of the Oneida and Tuscarora … Indians, adhered faithfully to the United States, and assisted them with their warriors; and in consequence of this adherence and assistance, the Oneidas and Tuscaroras, at an unfortunate period of the war, were driven from their homes, and their houses were burnt and their property destroyed: And as the United States in the time of their distress, acknowledged their obligations to these faithful friends and promised to reward them: and the United States now being in a condition to fulfill the promises then made: the following articles are stipulated by the respective parties for that purpose…”

In January 1795, the Veterans Treaty was ratified by Congress. As a result the Oneidas received a cash settlement and sawmill. But the remainder of what was owed to the Oneidas — a church and gristmill – may never have been received as the Oneidas were still seeking both in 1805.