How did it transpire that an Oneida woman, living on a farm in Manlius, who sang an Oneida dirge for a deceased anthropologist in Rochester, ended up recording said lament in New Jersey for Thomas A. Edison in the 1920s? As circuitous as it may sound, the line between Oneida Elsie Elm and the famed inventor can be easily drawn. And connecting the dots proves fascinating.

So … first, let’s meet Elsie.

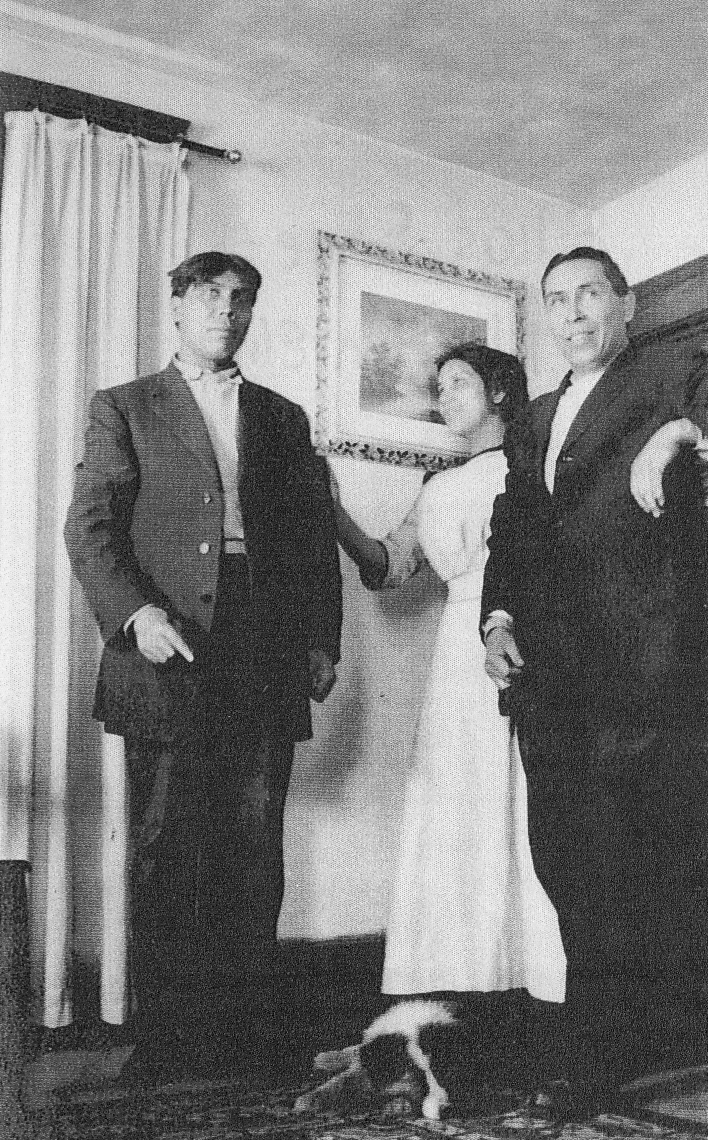

The telling of Elsie’s story is regrettably short, as little is known of her. What is documented are the particulars. She was born Jan. 6, 1883, to Oneidas Abraham and Margaret (Cornelius) Elm, both of whom are buried at Glenwood Cemetery in Oneida. Elsie’s maternal grandparents were Rev. Thomas and Elizabeth Cornelius; paternal grandparents were Baptist and Eva (John) Elm. Elsie had five siblings: Hattie, Elias, Charlie, Horton and Lydia, as well as a half-brother, Simeon Elm. Elsie never married.

Aside from Elsie’s placement on the Oneida rolls in 1886, 1901 and 1922, only fragments of her life are known, including her participation in a conference that began in Rochester and would result in her recording for Edison. But, we jump ahead …

Siblings Elias, Elsie and Horton Elm, c. 1910.

Elise, her brother Horton and fellow Oneida Bill Rockwell, along with additional Haudenosaunee representatives, journeyed to Rochester on Nov. 12, 1920, for the New York State Indian Welfare Society’s semiannual meeting. The society, begun in November 1919, was composed of both Haudenosaunee members and friends. According to a New York State Museum Bulletin, the society discussed mutual tribal needs; during their meetings, “… statistical records and accounts are given of reservation conditions and progress; historical accounts, appeals to progress, and other pertinent matters…” Meetings were held in several locales, including Syracuse and Malone, as well as Rochester.

The society’s November 1920 meeting was hosted by the Morgan Chapter of the New York State Archeological Association in Rochester. The chapter was named for anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan (1818 – 1881). Morgan had studied the Haudenosaunee and was adopted by the Seneca. He authored “The League of the Ho-de-no -su-nee or Iroquois” in 1851. Part of his research revolved around “human social organization,’’ and he was one of the initial people to study kinship systems.

According to the Morgan Chapter’s self-description in the “Researches and Transactions of the New York State Archeological Association” pamphlet, the organization is “an aggregation of men and women who have banded themselves together to promote historical study and intelligent research covering artifacts, rites, customs, beliefs, and other phases of the lives of the aboriginal occupants…”

Also in the association’s publication is an article by Robert Daniel Burns titled “An Iroquois Twentieth Century Ceremony of Appreciation,” which elucidates Morgan’s goals and, later, introduced Elsie:

“More than forty years ago, Lewis Henry Morgan warned his countrymen that the ethnic life of the Indian tribes was declining under the influence of American civilization: their arts and languages disappearing, and their institutions dissolving. His appeal to enter the rich field of discovery of the human records of the American aborigines has been answered. Here in Rochester, Morgan chapter is carrying on the work of research …”

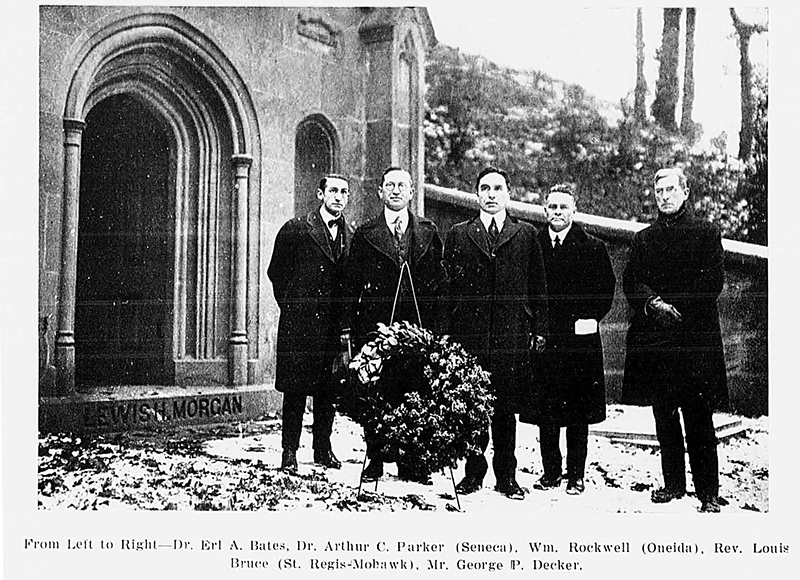

Thus it was that members of the Haudenosaunee came to appreciate Morgan and his efforts on their behalf. Thirty-nine years after his death, Elsie was among the group – Indian Welfare Society and Morgan Chapter members, as well as community leaders – to visit Morgan’s tomb at Mount Hope Cemetery. And it is at this juncture that our story actually begins.

On Sunday, Nov. 14, 1920, at Morgan’s gravesite, Burns wrote: “The orators opened their hearts; the fairest maiden of the Oneidas chanted the Appeal to the Great Spirit in the Oneida dialect just as her aboriginal ancestors sang it centuries ago in times of stress and thanksgiving…

“In the gathering were many members of the Morgan chapter, assemblymen and senators from the state legislature and others attracted to the ceremonies by the very novelty of the occasion. None came prepared for the sublime spectacle.”

Following an address by a chapter member, the president of the Morgan Chapter escorted Elsie to the tomb and, wrote Burns: “In a golden soprano, this Indian maid, facing the east, chanted the ancient Oneida Appeal to the Great Sprit. Her voice seemed to mellow the wind sweeping down the trail and through the oaks and spruces. Her arms outstretched, she made a dramatic figure as her voice awoke century-old memories of the Genesee. The beauty of the maiden, her modern dress of rich furs and the glowing pride of her race swelled the natural splendors of the scene as she sang ‘Da-ya-la-wajquat.’

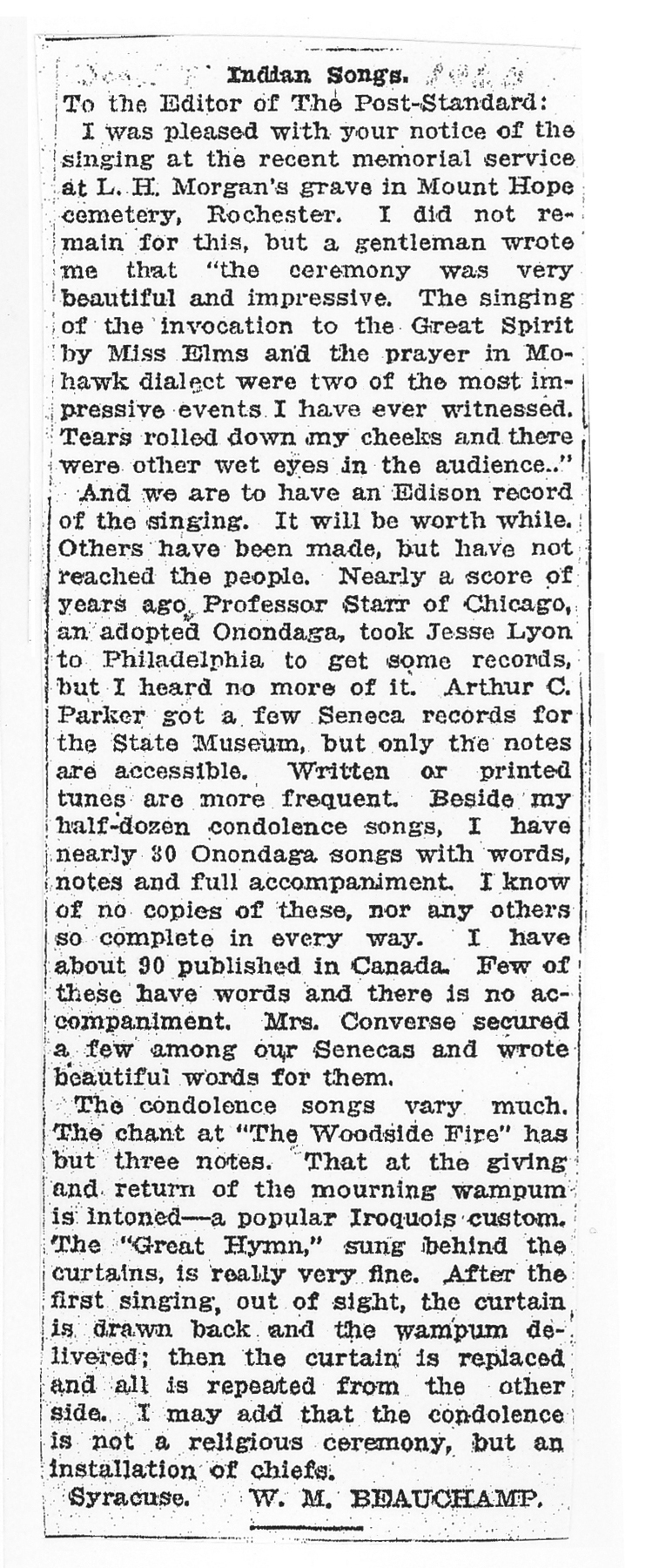

Word of Elsie’s singing in Rochester traveled. In an undated letter to the editor of the Syracuse Post-Standard, W.M. Beauchamp quoted a missive he had received from an attendee to the ceremony, stating:

“The ceremony was very beautiful and impressive. The singing of the invocation to the Great Spirit by Miss Elm and prayer in Mohawk dialect were two of the most impressive events I have ever witnessed. Tears rolled down my cheeks and there were other wet eyes in the audience.”

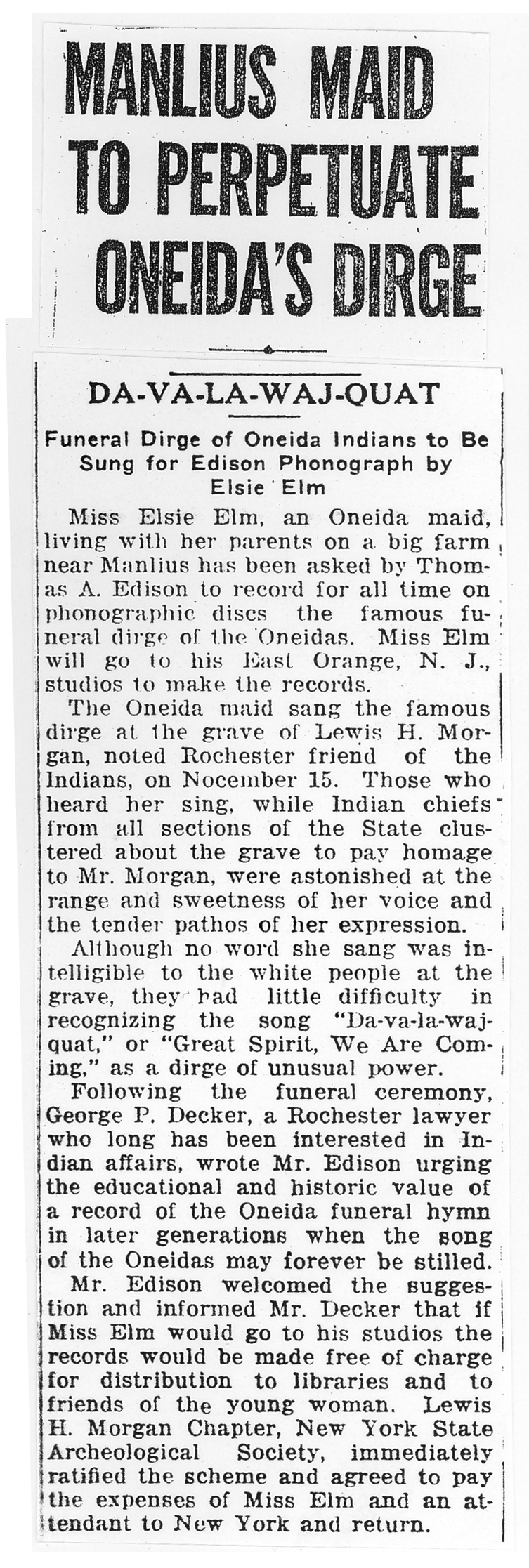

And from the Democratic Union in Rochester, Dec. 23, 1920:

“The Oneida maid sang the famous dirge at the grave of Lewis H. Morgan, noted Rochester friend of the Indians… Those who heard her sing, while Indian chiefs from all sections of the State clustered about the grave to pay homage to Mr. Morgan, were astonished at the range and sweetness of her voice and the tender pathos of her expression.

“Although no word she sang was intelligible to the white people at the grave, they had little difficulty in recognizing the song “Da-va-la-wajquat,” or “Great Spirit, We Are Coming,” a dirge of unusual power.

While testaments lauding the beauty of Elsie’s voice were abundant, how exactly did Edison hear of her? A Rochester lawyer named George P. Decker, who was “interested in Indian Affairs,” according to the Democratic Union’s Dec. 23, 1920 article, wrote to Edison urging him to record the funeral hymn for educational and historic value.

Thomas Edison agreed with Decker’s idea, stating that if Elsie would travel to his studio in East Orange, N.J., he would record her singing free of charge for distribution to libraries and to Elsie’s friends. The Morgan Chapter paid for Elsie’s travel expenses, as well as those of a companion’s.

By September 1921, the phonograph recording of Elsie singing “An Appeal to the Great Spirit” was heralded by the Madison County Historical Society. The Oneida Dispatch’s Sept. 23, 1921, edition noted the society’s program as a “unique and interesting entertainment… The phonograph record of an Oneida Indian dirge, entitled “An Appeal to the Great Spirit,” which Elsie Elm sang for the Edison company … furnished a musical section of the evening’s program of rare interest.”

Elsie’s recording is retained by the Edison Museum, which provided a copy to the Nation; a portion of it may be heard here.

(EDITOR’S NOTE: This story originally appeared in the April/May 2009 edition of The Oneida, Issue 3, Volume 11. Special thanks to Becky Karst, daughter of Martin Johns, Turtle Clan, for sharing her research on this story).