A volcanic eruption in Indonesia more than 200 years ago affected climate around the globe (researchers believe), leaving decimated crops in its wake. The Oneida suffered, too, enduring the failure of their Indian corn. A man named Dr. Jonas Baldwin offered friendship and aid to the Oneida during this difficult time and the friendship – as well as a lovely gift – would be reciprocated.

In 1816, commonly referred to in lore as “the year without summer,” Mt. Tambora produced history’s biggest explosive volcanic eruption, according to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Temperatures across the world were lower than normal with snow falling in some areas in July.

How cold was it? For that answer, we look to “Pierce on the Weather,” a publication that chronicled weather conditions until 1846. According to “The Friend,” an 1873 Society of Friends book, “Pierce on the Weather” was the ultimate source to “get our old time comparisons.”*

To understand the circumstances through which the Oneida and others survived during the “the year without summer,” here is a breakdown by month as published in an unknown Rochester newspaper, which stated that the listing was “extracted in part from ‘Pierce on the Weather’”:

“January was mild – so much so as to render fires almost needless in sitting-rooms. December preceding was very cold.

“February was not very cold. With the exception of a few days, it was mild, like its predecessor.

“March was cold and boisterous, the first half of it; the remainder was mild.

“April began warm, and grew colder as the month advanced, and ended with snow and ice, with a temperature more like winter than spring.

“May was more remarkable for frowns than smiles. Buds and fruits were frozen; ice formed half an inch in thickness, corn was killed; and the fields were again and again replanted, until deemed too late.

“June was the coldest ever known in this latitude. Frost and ice and snow were common. Almost every green herb was killed; fruit nearly all destroyed. Snow fell to the depth of ten inches in Vermont and in Maine; three inches in the interior of New York. It fell also in Massachusetts.

“July was accompanied by frost and ice. On the morning after the 4th, ice formed of the thickness of a common window glass, throughout New England, New York, and some parts of Pennsylvania. Indian corn was nearly all killed; some favorably situated fields escaped. This was true of some of the hills of Massachusetts.

“August was more cheerless, if possible, than the summer months already passed. Ice was formed half an inch in thickness. Indian corn was so frozen, that the greater part of it was cut down and dried for fodder. Almost every green thing was destroyed in this country and Europe. Papers from England said, ‘It will ever be remembered by the present generation, that the year 1816 was a year in which there was no summer.’ Very little corn in the New England and Middle states ripened; farmers supplied themselves from the corn produced in 1815 for seed in the spring of 1817. It sold for $4 to $5 a bushel.

“September finished about two weeks of the mildest weather of the season. Soon after the middle, it became very cold and frosty; ice forming a quarter of an inch in thickness.

“October produced more than its usual share of cold weather; frost and ice common.

“November was cold and blustering; snow fell so as to make sleighing.

“December was mild and comfortable.

“Very little vegetation matured in the Eastern and Middle states. The sun’s rays seemed to be destitute of heat throughout the summer; all nature was clad in a sable hue; and men exhibited no little anxiety concerning the future of this life.”

A desolate tale, for sure. A time of severe deprivations with fears of starvation.

Outlined in the book “Onondaga, Or Reminiscences of Earlier and Later Times,” by Joshua Victor Hopkins Clark and published in 1849, the following account is given:

“… with no provisions for the then approaching winter, they [Oneidas] were in danger of being cut off by famine. Under these circumstances, a deputation of chiefs, from the Oneida [Indian] Nation, were sent to Dr. Baldwin, (they knowing him to be a man of wealth and benevolence,) to request him to furnish them with provisions for the winter. After some inquiries as to their necessities and number, Dr. B. agreed to furnish provisions for one-half of the nation. Early in the winter, therefore, they came on, about 250 in number, and encamped in a wood in the vicinity of the village, and near where the railroad now crosses the road leading to the new bridge, and remained there until the next spring, drawing their rations daily, like a small army.

Dr. Baldwin’s well-timed benevolence saved these destitute people from starvation, while the remainder of the nation were fed and carried through the winter by the charity of other individuals.

During the winter, Harvey Baldwin, (late mayor of Syracuse,) second son of Dr. B., being on a visit home, permission was asked by the chiefs to adopt him as their son, which request being granted, they assembled in grand council, and after great ceremony, such as is customary with Indians on occasions of this kind, gave him the name of “Cohongoronto,” by which name he is still known among the Oneidas, and which interpreted, signified a boat having a sharp prow, constructed for the navigation of rapid waters, and which was intended as emblamatical of the profession of law, in the study of which he was then engaged.”

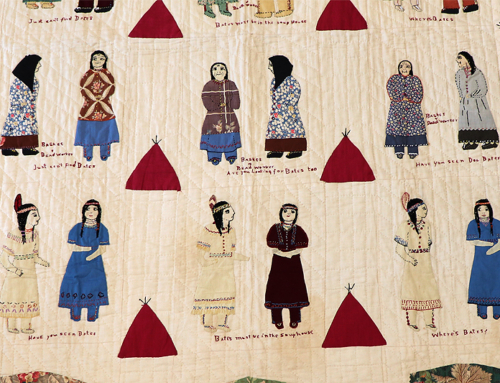

A close-up of the intricate beadwork displayed on a coat made by the Oneida in the early 1800s and given as a gift to Syracuse’s first mayor, Harvey Baldwin. Photo: Onondaga Historical Association Museum & Research Center, Syracuse, NY.

The Oneida also presented Harvey Baldwin, who later became the first mayor of Syracuse, with a beaded deerskin coat. The coat was given to the Onondaga Historical Society by Harvey’s great-grandson, John A. Morton, Jr. in 1949.

* “A compiler of “Weather Statistics” would think his library illy furnished did he not possess a copy of “Pierce on the Weather.” From this source we all get our old time comparisons. The labors of “Pierce” in this capacity ceased with the year 1846, and from other sources the following has been compiled.” From The Friend, 1873, Society of Friends

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2010 edition of The Oneida newsletter.