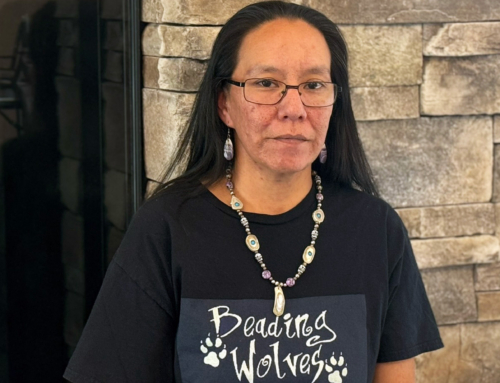

By Kandice Watson (Wolf Clan)

Documentarian, Oneida Indian Nation

The Great New York State Fair has been an integral part of New York State’s culture and history for many years. In 1832, the New York State Agricultural Society was founded by a group of farmers, legislators, and others to promote agricultural improvements and local fairs. This group held the first New York State Fair in Syracuse in 1841, which was a two-day event with husbandry shows, speeches by notable guests, a plowing contest and samples of manufactured goods for the farm and home. The second fair was held in Albany, and then from 1842-1889, the fair traveled around to various cities in New York State including Auburn, Buffalo, Elmira, New York City, Poughkeepsie, Rochester, Saratoga Springs, Watertown and Utica. The Indian Village was not an original component of the State Fair and was added in 1928.

In 1889, Syracuse Land Co. donated 100 acres of land in Geddes to the Agricultural Society. The land was located near railroad tracks, which helped to facilitate exhibit transport. The Agricultural Society immediately began to construct permanent buildings on the property, which quickly became too costly for the small group. They sought help from New York State, which purchased the property and instituted an 11-member State Fair Commission appointed by the governor to run the fair in 1899. Throughout the next few decades, many permanent buildings were erected on the site.

In the early twentieth century, Americans had still not lost their nostalgia for American Indian culture and therefore, “Wild West Shows” were all the rage throughout the country. Many Indian Nations by this time were displaced and individuals were performing in these shows for economic reasons. The New York State Fair also had an exhibit related to American Indians, although it is uncertain as to when this exhibit exactly came into existence. A 1920 newspaper article states that the Indian Village was to be omitted that year at the fair due to an accident to one of the leaders on the reservation. It is unclear what accident occurred, or even what reservation they are referring to, but we do know a previous Indian exhibit had been held there at least one year prior, in 1919.

In 1925, an Indian Show was held in a rented tent on the current lands of the Indian Village at the fairgrounds. The intent was more of a show, done to allow the patrons to see and hear real, live Indian people. This was very similar to the Wild West shows, and more than likely, organized by non-Indian people with Indians merely acting as performers in skits.

Although most Indians say they enjoyed performing in these shows, they longed to stay at home. If a festival could be held on their own reservations, they could tell their own story, relay the information that they felt was important and charge admission. In 1923, Chief William Rockwell (Oneida) began holding the Iroquois Indian Primitive Industrial Exposition on the 32 acres in Oneida. The second annual show brought more than 1,000 visitors and was held annually for about 5 years until around 1928. Coincidentally, the Indian Village at the New York State Fair was underway in 1928, about the same time that Rockwell stopped doing his exposition. We certainly cannot say that his exposition was “moved to the fairgrounds,” but it does seem as if they happened at the same time.

A Village Takes Shape

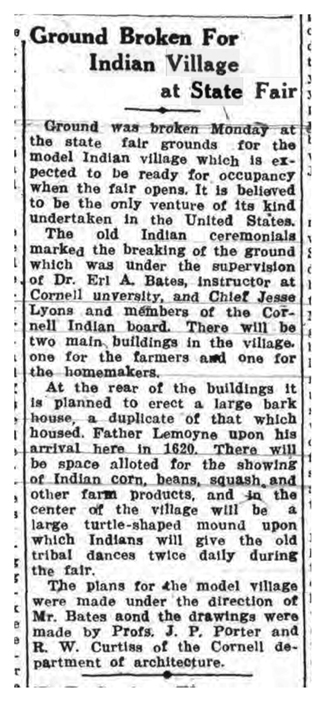

In 1928, ground was officially broken for the current site of the Indian Village at the New York State Fairgrounds under the direction of Cornell professor Earl A. Bates, Chief Jesse Lyons (Onondaga) and members of the Cornell Indian Board. There were two buildings planned for the village at that time: one for farmers and one for the homemakers. At the rear of these buildings, a bark house was to be erected in the typical style of a longhouse, similar to the one Father LeMoyne had lived in upon his arrival in the area in 1620. In addition to the buildings, space was to be allotted for the growing of corn, beans and squash in the traditional companion-style planting method and land was reserved for the development of a Turtle Mound where Indians would perform dances twice daily. In addition to dancing, a lacrosse game was planned between the tribes on a field located within the village.

These plans were completed very quickly, and by early June of the following year, these areas were being restored and made ready for exhibition during the fair in the fall, as noted in a 1929 Syracuse American newspaper article. This article also makes mention of a separate Bear Mound located near the Turtle Mound, which was never heard of again. Perhaps the Bear Mound could not be repaired in time for the fair and was eliminated? We may never know.

During the early years of the Indian Village, many customs were followed that were leftovers from the Wild West Show era. A couple examples of these were the performance of a mock traditional Indian wedding ceremony and the choosing of a man to become a “blood brother” to the Indians, complete with an honorary Indian name. These two displays were very popular amongst non-Indians and drew large crowds at the time. A 1937 article from an unknown newspaper tells us that Mr. and Mrs. Stanley (Rita Bennett) Pierce, of Nedrow, were remarried in the mock wedding ceremony in their tribal finery.

In addition to dancing, adoption rituals and mock weddings, Americans were fascinated with Indian foods, thus it was decided between Chief Rockwell and Mr. Bates, with approval of the other tribes, to open a Soup House in the village to serve samples from the traditional Indian diet. A Brookfield Courier newspaper article tells us that the Soup House was opened in 1930 and was headed by homemaker Minnie Shenandoah (Onondaga) who chose a menu consisting of woodchuck pie, blueberry waffles, old-time corn and bean soup, Indian breads, Johnny cake and other examples of Indian cookery. Today, the Soup House remains an important place in the village for social gatherings and a good place to enjoy home-cooked foods.

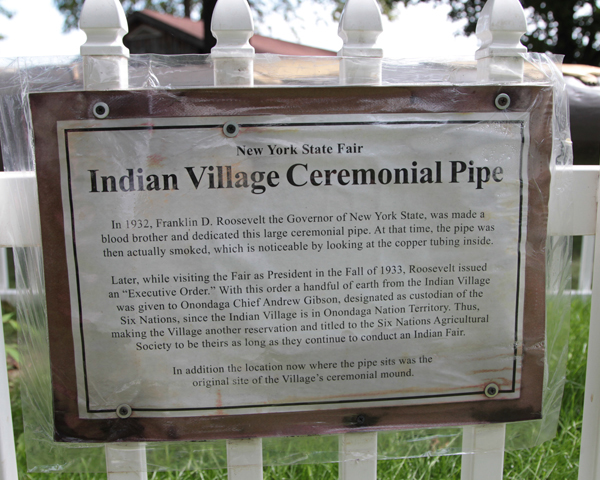

A Pipe, A Quilt and an Ear of Corn

Chief Rockwell added a central exhibit to the Village in 1932. He decided to carve a large peace pipe for the village and worked on the pipe throughout the year so it would be ready in the fall. He spent many long days carving the pipe, and was often besieged by curious spectators in the area. An article from an unknown newspaper states that he would rise every day at 4 a.m. to get some work done before the onlookers became too many. The bowl of the pipe was made from applewood and the stem was carved from basswood. The bowl was 23 inches high with a 16 inch opening and the stem of the pipe was 16 feet long. He carved the 8 clans of the Haudenosaunee on the stem and also ensured that the pipe could be smoked. The pipe remains an important part of the Indian Village to this day.

Governor Franklin Roosevelt dedicated the large ceremonial pipe while he was still the governor of New York State in 1932, and in the following year , as president, he officially granted the Six Nations Agricultural Society an easement title of the Indian Village to be theirs, as long as they conduct an Indian Fair on the land. A lacrosse game was held for three years in the village, but was deemed too dangerous to spectators without some type of barrier fencing. The Six Nations Agricultural Society gave permission in 1936 for the 4-H Building to be erected in the spot of the lacrosse field.

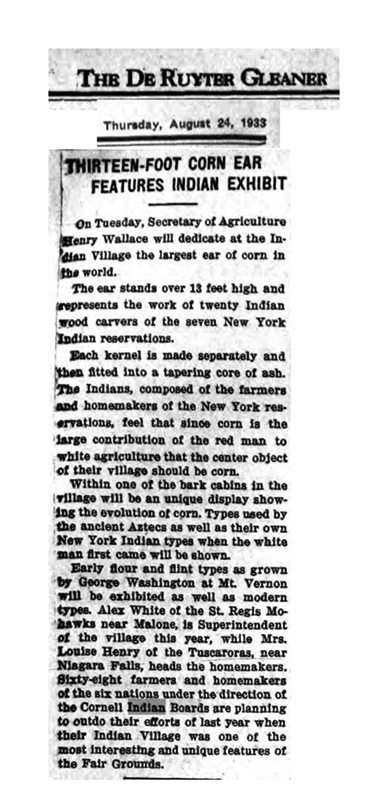

1933 brought a new “exhibit” to the Indian Village in the form of a huge ear of corn. According to a 1933 article in The DeRuyter Gleaner, the ear of corn was 12 feet high and each individual kernel was hand-carved and then fitted into a tapering core of ash. An extensive corn exhibit was also featured that year in one of the log houses, which showed ancient Aztec corn, traditional Iroquois versions and modern varieties of flour and flint types grown by George Washington at Mt. Vernon. This ear of corn was the result of much planning and thought from Oneida Chief Chapman Schanandoah, who was very involved with early Indian Village activities.

Earl Bates was very influential throughout the years at the village. In 1939, Oneida Emily Johnson saw for herself how important Mr. Bates was to the village. She had found herself under the weather that year at the fair, laid down to rest and was continuously hearing the question “Where’s Bates” asked over and over by many different people who needed his expertise or advice on some matter. It was then that she decided she would do something to honor Mr. Bates for his help. She made a quilt for him, working on it throughout the year, adding pictures of various village buildings and locations in an intricate beaded pattern. The Soup House, Turtle Mound and other prominent sites were pictured. The question “Where’s Bates?” was also beaded several times onto the quilt. The quilt was displayed in the Women’s Building in 1940 and was given to Mr. Bates’ son Jonathon at the closure of the fair. The current location or existence of the quilt is unknown at this time.

A 1941 Syracuse Herald Journal article discusses the expansion of the Indian Village with the addition of an Indian Women’s Dormitory and the enlargement of the arboretum, which was under the supervision of Chief Rockwell at the time. Rockwell had served as the village superintendent for a few years, but in 1941, Russell Hill (Seneca) was the Village Superintendent. Prior to Rockwell, Mohawk Alex White had served in the role from 1933-1937.

By 1951, the Cornell Indian Board was not as popular in home communities as it had once been. Those sitting on this board were placed there by the various tribal councils and did not accurately represent the farmers or homemakers on the reservations. It was decided then to form the Six Nations Agricultural Society with members paying $1 or more in yearly dues and electing officers. The new society would take over the Indian Village at the State Fair and develop means to operating the popular Indian exhibition at the annual fair. This club would also work closely with 4-H organizations with its work among the New York Indians.

In 1955, the New York State Fair Trailerama visited 18 New York cities and traveled over 1,000 miles to popularize and promote the fair and encourage attendance. The Trailerama consisted of a five trailer caravan. Each trailer was 20 -50 feet long and housed a sampling of a Fair exhibit. One trailer housed Indian exhibits and relics, and was in the charge of Chief Rockwell. Traveling with Rockwell in the exhibit were Tuscarora Indian Village Princess Claudia Reed and her mother, Lucinda Reed.

Claudia was the fourth Indian Princess chosen to represent the Indian Village. It seems the first princess was chosen in 1952 – Frieda Williams, who was also Tuscarora. The second princess was Maribel Watt, Alleghany Seneca in 1953 and Jessie Crouse, Cattaraugus Seneca, was the third in 1954. Many women have been bestowed with the honor of New York State Fair Indian Village Princess, and all followed in the footsteps of these strong women. (Editor’s note: the author of this article, Kandice Watson, served as the Indian Village Princess in 1985)

Two new buildings at the Indian Village were dedicated in 1972. This was Oneida year, and Princess Elizabeth Robert participated in the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Iroquois Art Center, where different pictures of Indian life and art were displayed. The Patterson Building had undergone renovations and was re-opened with each of the Six Nations presenting their own exhibit that was reflective of their own culture and history. Also that year, an expanded herb garden was featured in the village with medicinal herbs and several strains of Indian tobacco.

Changes Bring Improvements as the Village Lives On

In 1975, the New York State Fair Indian Village celebrated its 50th anniversary. Russell Hill was still superintendent and Jacqueline John (Alleghany Seneca) served as the Indian Village Princess. As was tradition, a “blood brother” ceremony was performed on the Turtle Mound on Indian Day and The Iroquois Band entertained fairgoers.

The Indian Village remained relatively unchanged for several years until 1982 when the village was given a 5-year, $250,000 restoration with plans for the addition of 6 new huts and a 46-bed dormitory. A 1982 Syracuse Herald American article writes of a discussion held with then Superintendent Lloyd Elm (Onondaga) regarding the location of the dormitory. There was some controversy over whether the dormitory should be built on land owned by the society or land owned by the state. In the past, Indians would simply have complied with the state’s plan to put the dormitory on Indian land, Elm says. “The leadership of the society is more resistant today.”

After these improvements, the fair stayed relatively consistent for the next few decades, and then in 2011, plans were made to construct another authentic longhouse. The Six Nations Agricultural Society, Tuscarora Environmental Department and the State University College of Environmental Science and Forestry brought the longhouse to life after many years of research. Jordan Cooke, Assistant Superintendent, said “It is based on archaeological excavation and is a 17th-century bark longhouse.” Educational displays and talks are given throughout the fair inside the longhouse, which depicts the lifestyle of 17th century Haudenosaunee.

In 2015, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a $50 million plan to renovate the State Fair Grounds. A portion of this money, $750,000, was earmarked to renovate the Indian Village. One area in dire need of attention was the Turtle Mound space where dances are performed three times daily. The new Turtle Mound was unveiled at the 2017 State Fair, and visitors were amazed at the transformation. New landscaping, signage and an updated stage for dancers was a welcoming sight for repeat Indian Village visitors. The Soup House was also upgraded with improvements made to the kitchen and with the extension of the porch. More benches and seating were installed throughout the village and new entrances were designed to be more welcoming.

Throughout the years, the Indian Village has remained a constant in the lives of the Haudenosaunee in late summer. Superintendents and Nation Vice Presidents come and go, but the village remains. The trees scattered throughout the area lend to the park-like feel, where everyday stresses of the fair and life melt away. People gather around the benches surrounding the Turtle Mound and “hold court” for a few hours while they reminisce with their friends and relatives about old times. The Great New York State Fair Indian Village holds memories very dear to our hearts and one cannot imagine the fair without the village.