Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Lucretia Mott – all pioneers of the women’s rights movement in the 19th century – drew inspiration for their vision of women as full participants in American society from the matrilineal culture of the Haudenosaunee.

Sally Roesch Wagner, a nationally renowned historian of the feminist movement and executive director of the Gage Foundation (named for Matilda Joslyn Gage) in Fayetteville, N.Y., is the author of Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Influence on Early American Feminists (Native Voices, 2001). In her book and several essays, Wagner explores how close association with women of the Six Nations inspired suffragists with the vision of a society in which women had the same rights and responsibilities as men.

“I could not fathom how they dared to dream their revolutionary dream,” Wagner wrote. “Whatever made them think that human harmony – based on the perfect equality of all people, with women absolute sovereigns of their lives – was an achievable goal?”

The answer, she wrote, was right in front of her, in the suffragists’ own words, though it took Wagner a while to see it: “They caught a glimpse of the possibility of freedom because they knew women who lived liberated lives, women who had always possessed rights beyond their wildest imagination – Iroquois women.”

Here’s a brief look at how the American feminists of the 1800s viewed the lives and freedoms of their Haudenosaunee sisters, and how the Haudenosaunee example inspired the leaders of the women’s rights movement.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton From Sally Roesch Wagner’s essay, The Untold Story of the Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists:

“Stanton, for instance, sat across the dinner table from Oneida women during her frequent visits to her cousin, the radical social activist Gerrit Smith, in Peterboro. Smith’s daughter, also named Elizabeth, was first to shed the 20 pounds of clothing that, fashion dictated, should hang from a white woman’s waist, dangerously deformed from corseting. The reform costume Elizabeth Smith adopted (named the “Bloomer” after the newspaper editor who popularized it) bore an uncanny resemblance to the loose-fitting tunic and leggings worn by the two Elizabeths’ Native American friends.

Matilda Joslyn Gage From Sally Roesch Wagner’s essay, The Untold Story of the Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists:

“Gage, appointed by a women’s rights convention in the 1850s, worked on a committee with New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley to document the woefully few jobs open to white women. Meanwhile, she knew hardy, nearby Onondaga women who farmed corn, beans, and squash – nutritionally balanced and ecologically near-perfect crops called the Three Sisters by the Haudenosaunee…”

Lucretia Mott From Sally Roesch Wagner’s essay, The Untold Story of the Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists:

“Lucretia Mott and her husband, James, were members of the Indian committee of the Philadephia yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends. For years, this committee of Quakers befriended the Seneca, setting up a school and model farm at Cattaraugus and helping them save some of their territory from unscrupulous land speculators. In the summer of 1848, Mott spent a month at Cattaraugus witnessing women share in discussion and decision-making as the Seneca nation reorganized their governmental structure. Her feminist vision fired by that experience, Mott traveled that July from the Seneca nation to nearby Seneca Falls, where she and (Elizabeth Cady) Stanton held the world’s first women’s rights convention.

“When the Seneca adopted a constitutional form of government, they retained the tradition of full involvement of the women. Under their constitution, no treaty could be valid without the consent of three-quarters of the “mothers of the nation.”

Women’s Safety From Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Influence on Early American Feminists, by Sally Roesch Wagner:

“Rev. M.F. Trippe, long a missionary on the (Seneca) reservations, told a New York City reporter:

‘Tell the readers of the Herald that… they have a sincere respect for women – their own women as well as those of the whites. I have seen young white women going unprotected about parts of the reservations in search of botanical specimens best found there and Indian men helping them. Where else in the land can a girl be safe from insult from rude men whom she does not know?’

Political involvement From Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Influence on Early American Feminists, by Sally Roesch Wagner:

“Arthur C. Parker reminded non-Native readers in 1909:

‘Does the modern American woman [who] is a petitioner before man, pleading for her political rights, ever stop to consider that the red woman that lived in New York state five hundred years ago had far more political rights and enjoyed a much wider liberty than the twentieth century woman of civilization?’

Rights of Property Donald Grinde, Jr., professor of American Indian Studies and chair of the Department of American Studies at SUNY Buffalo, recounted this story in a 2002 interview with the journal Spirit of Ma’at:

Elizabeth Cady Stanton describes how, as a young girl on an Iroquois reservation — she was twelve or thirteen — she saw a man come up, and the mother of her Indian playmate went outside and talked to this man for a half hour or more. Then he handed her some money, they went to the barn and took a horse out, and he rode off on the horse.

Stanton asked the mother what had happened, and the woman said, “Well, I sold the man one of my horses. We negotiated the price, and then he gave me the money, and then he left with the horse.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton said, “What will your husband say when he gets home?”

The woman said, “Well, it was my horse, and I can do with it as I please.”

For a young Euro-American woman, it was quite a revelation that this was possible, that a woman could behave in this way, holding property and disposing of it without the approval of a husband or father.

Under U.S. laws at the time, married women were legally dead; they had no rights to property, to their earnings when they worked or to any inheritance. They didn’t even have rights to their children; a husband could “will away” guardianship to whomever he chose. Comparisons with Iroquois Women From Sally Roesch Wagner’s essay, The Untold Story of the Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists:

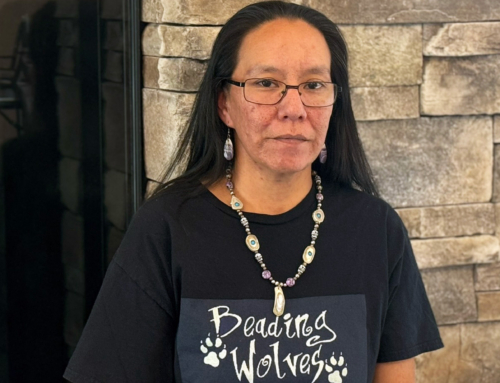

“…imagine how the founding feminists felt as they beheld the Iroquois world. For instance, shortly after Matilda Joslyn Gage was arrested in 1893 at her home in New York for the ‘crime’ of trying to vote in a school board election, she was adopted into the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk nation and given the name Karonienhawi (‘Sky Carrier’)… And Elizabeth Cady Stanton – called a heretic and worse for advocating divorce laws that would allow women to leave loveless and dangerous marriages – admired the model of divorce Iroquois style: ‘No matter how many children or whatever goods he might have in the house,’ Stanton informed the national council of women convention in 1891, the ‘luckless husband or lover who was too shiftless to do his share of the providing… might at any time be ordered to pick up his blanket and budge; and after such an order it would not be healthful for him to attempt to disobey.’

Greater Rights of Indian Women In 1888, Alice Fletcher, a noted white ethnographer, addressed the International Council of Women and spoke of the greater rights of American Indian women, pointing out that those women also realized they would lose many of their rights if they became U.S. citizens. Fletcher said one Indian woman told her:

“As an Indian woman, I was free. I owned my home, my person, the work of my own hands, and my children should never forget me. I was better as an Indian woman than under white law.”