The Haudenosaunee Confederacy preceded the formation of the United States by centuries. Many of the tenants put forth by the Nations of the Confederacy are regarded as precursors to the precepts of America as laid down by its founding fathers. The following is an excerpt from the book Forgotten Founders: Benjamin Franklin, the Iroquois and the Rationale for the American Revolution, by Bruce E. Johansen:

“Late in 1978, the time came to venture the topic for my Ph.D. dissertation in history and communications. I proposed an investigation of the role that Iroquois political and social thought had played in the thinking of Franklin and Thomas Jefferson…

“After several months of research, I found two dozen scholars who had raised the question since 1851, usually in the context of studies with other objectives. Many of them urged further study of the American Indians’ (especially the Iroquois’) contribution to the nation’s formative ideology, particularly the ideas of federal union, public opinion in governance, political liberty, and the government’s role in guaranteeing citizens’ well-being — “happiness,” in the eighteenth-century sense…

“Immersion in the records of the time had surprised me. I had not realized how tightly Franklin’s experience with the Iroquois had been woven into his development of revolutionary theory and his advocacy of federal union. To understand how all this had come to be, I had to remove myself as much as possible from the assumptions of the twentieth century, to try to visualize America as Franklin knew it…

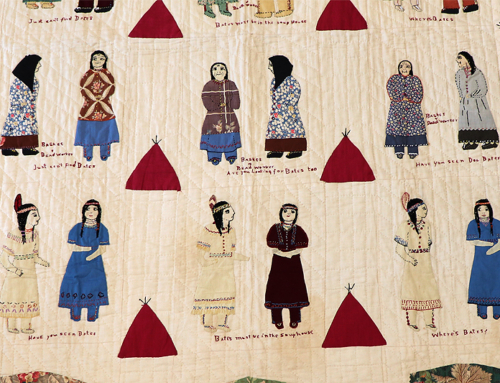

“I would need to describe the Iroquois he [Benjamin Franklin] knew, not celluloid caricatures concocted from bogus history, but well-organized polities governed by a system that one contemporary of Franklin’s, Cadwallader Colden, wrote had “outdone the Romans.” Colden was writing of a social and political system so old that the immigrant Europeans knew nothing of its origins — a federal union of five (and later six) Indian nations that had put into practice concepts of popular participation and natural rights that the European savants had thus far only theorized. The Iroquoian system, expressed through its constitution, “The Great Law of Peace,” rested on assumptions foreign to the monarchies of Europe: it regarded leaders as servants of the people, rather than their masters, and made provisions for the leaders’ impeachment for errant behavior. The Iroquois’ law and custom upheld freedom of expression in political and religious matters, and it forbade the unauthorized entry of homes. It provided for political participation by women and the relatively equitable distribution of wealth. These distinctly democratic tendencies sound familiar in light of subsequent American political history — yet few people today (other than American Indians and students of their heritage) know that a republic existed on our soil before anyone here had ever heard of John Locke, or Cato, the Magna Charta [Carta], Rousseau, Franklin, or Jefferson…

“Out of English efforts at alliance with the Iroquois came a need for treaty councils, which brought together leaders of both cultures. And from the earliest days of his professional life, Franklin was drawn to the diplomatic and ideological interchange of these councils — first as a printer of their proceedings, then as a Colonial envoy, the beginning of one of the most distinguished diplomatic careers in American history. Out of these councils grew an early campaign by Franklin for Colonial union on a federal model, very similar to the Iroquois system. Contact with Indians and their ways of ordering life left a definite imprint on Franklin and others who were seeking, during the prerevolutionary period, alternatives to a European order against which revolution would be made. To Jefferson, as well as Franklin, the Indians had what the colonists wanted: societies free of oppression and class stratification. The Iroquois and other Indian nations fired the imaginations of the revolution’s architects. As Henry Steele Commager has written, America acted the Enlightenment as European radicals dreamed it. Extensive, intimate contact with Indian nations was a major reason for this difference.

“This book has two major purposes. First, it seeks to weave a few new threads into the tapestry of American revolutionary history, to begin the telling of a larger story that has lain largely forgotten, scattered around dusty archives, for more than two centuries. By arguing that American Indians (principally the Iroquois) played a major role in shaping the ideas of Franklin (and thus, the American Revolution) I do not mean to demean or denigrate European influences. I mean not to subtract from the existing record, but to add an indigenous aspect, to show how America has been a creation of all its peoples.

“In the telling, this story also seeks to demolish what remains of stereotypical assumptions that American Indians were somehow too simpleminded to engage in effective social and political organization.”