This article originally appeared in The Oneida newsletter, issue 2, volumes 13, February 2011.

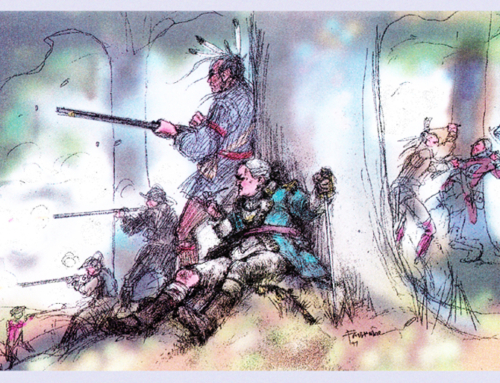

The name of Hanyery (or Han Yerry) is synonymous within the Oneida Indian Nation with the Battle of Oriskany. His valor at this pivotal battle of the Revolutionary War is legendary. Though wounded, he continued to fight with the help of his wife, who loaded his gun. But what of his life off the battlefield? What manner of man was he? A few clues can be gleaned from the pages of Forgotten Allies, wherein Joseph T. Glatthaar and James Kirby Martin’s research conjures a flesh-and-blood man – husband, father, neighbor and warrior.

Hanyery Tewahangarahken, “He Who Takes Up the Snow Shoe,” was born in 1724 and would eventually ascend to the position of chief warrior of the Wolf Clan. Even as a young man, he was noted for his “exceptional courage and coolness in combat.” Circa 1750, he married Tyonajanegen, also known as Two Kettles Together. The couple lived in Oriska as part of the founding Oneidas of that village, raising three sons (Peter, Jacob and Cornelius) and a daughter (Dolly).

At Oriska, Hanyery and his family thrived on a large farm, selling their produce to travelers stopping off at the Oneida Carrying Place and the inhabitants of Fort Stanwix. According to the authors, the family dwelled in a framed house and had a barn, 15 horses, six cattle, 20 hogs, two sheep, six turkeys and 100 chickens. In addition to the menagerie, they grew an assortment of crops and had farm implements that included a wagon and sleigh. Meals were cooked in brass and copper kettles, and guests ate off of pewter plates with pewter spoons. Although Hanyery had become wealthy in terms of material possessions around his home, very few Oneida families at the time had European furniture. Oneidas still kept a central fire in the middle of the room with simple sleeping bunks on the walls of the house.

As Glatthaar and Martin noted, “Han Yerry had become one of the wealthiest of all Oneidas.”

When the British coerced the Oneidas into ceding a section of their territory, including lands encompassing Oriska, in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, the villagers were incensed. Thus, by 1777 the Oriska Oneidas, which included Hanyery’s brother Han Yost Thahoswagwat (or His Lip Followed Him), decided to fight along with Hanyery on the rebel side.

By the time he fought in the Revolutionary War, Hanyery was in his fifties and was recalled by one observer as an “ordinary sized” man and “quite a gentleman in his demeanor.” His Oneida friend Hendrick Smith said of him, “Han Yerry was too old for the Service, yet used to go fearlessly into the fights.” Bravery’s age is limitless.

1779 brought Hanyery a commission from the fledgling United States government as captain to the Oneidas. The rank was given to him on the advice of the chief warriors of the Oneida. It was a deserved recognition for Hanyery, who had “distinguished himself at Oriskany and Saratoga and led the Indian column to Valley Forge.” And it was at Valley Forge that Hanyery was asked to sup with George Washington.

In addition to his fighting prowess, Hanyery was also a signer and participant at many conferences held at Johnson Hall, Fort Stanwix and Fort Herkimer.

Repercussions for the Oneidas’ decision to side with the rebels were forthcoming, however. Following the Battle of Oriskany, other Haudenosaunee, who had sided with the British, burnt the village of Oriska to the ground in retribution for the Oneidas’ choice. Hanyery’s home and all his possessions were also destroyed in the tumult. After the burning of Oriska in September 1777 by Joseph Brant and other pro-British Indians, Hanyery moved to Canajoharie and lived in Molly Brant’s house for a few months as compensation for her brother’s destruction of his village.

When the war was over, Hanyery once again held a leadership role in an Oneida village, but not his former Oriska.

He died around 1794, predeceasing his wife and battlefield companion, Two Kettles Together, by nearly three decades.