Gratitude and service are what drive Donald Gaines (Wolf Clan). They are values that transcend any culture. He’s waited his entire adult life for an opportunity to pay it forward for the Oneida Indian Nation and its future generations. Now, at 32 years old, he is the Nation’s new youth programs coordinator – a position where he hopes he can instill those same values.

The path to his new role was not conventional. His great-grandparents faced challenges that many other Oneidas of that generation may remember, or even experienced themselves. His great-grandmother, Mabel Hill (Wolf Clan), and great-grandfather, Allison Printup, lived in poverty and had their nine children taken away from them at an early age. Some were put into the foster care system while others were sent to boarding schools, like the Thomas Indian School in Western New York or the Elmcrest Children’s Center in Syracuse.

But Donald’s grandmother, Wanda Latta (Printup), was adopted by Thelma Youngs and moved to Michigan. It’s a path that drastically changed her way of life, as well as her eventual children’s upbringing. Wanda had five children of her own, including Thelma Lou, Donald’s mother.

“I’m sure it was very strained – they all dealt with it in different ways,” Donald said. “My grandmother was the negative stereotype. She drank a lot. So it was my mom who really was the one who tried to reconnect with the Nation.”

With three generations living away from Oneida homelands – and Wanda growing up in a non-Native household – it was difficult for Donald’s family to connect with their Haudenosaunee roots and culture. But Thelma Lou never forgot where she came from.

She moved to Fayetteville, North Carolina for a job and planted her own roots to start a family. She met her husband of nearly 30 years, Eric Gaines, a U.S. Army paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division, while he was on active duty at Fort Bragg. Eric retired from the Army after 21 years of service that included a deployment to Iraq in 2003; a legacy of service and selflessness that Thelma Lou and Donald are both proud of.

Taking advantage of the Oneida Indian Nation’s Scholarship Program, Thelma earned a master’s degree from the University of North Carolina-Pembroke and now teaches young children in primary school. Her first degree in American Indian Studies led her to find a reliable support system through the Lumbee Tribe and the Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, which ultimately helped push Donald to pursue higher education.

“I’m coming from being immersed in Lumbee culture, and of course, the Cherokees,” he said. “So I’m used to these large communities being right next door and a big part of my lived experience.”

Donald attended Fayetteville Technical College, where he received his associate degree before attending UNC-Pembroke. He chose to major in American Indian Studies as well and added a minor in Management.

“My mom has always been an inspiration to me,” Donald said. “She didn’t choose American Indian Studies for her career. She did it because she wanted to know about her heritage and sought to make that connection.”

Donald said it was such a huge moment for her – and his family. She was the first of her siblings to go to college, and he wanted to follow in her footsteps. Donald is the only one of his generation, on either side of his family, to get a college degree, too. Once he enrolled at UNC-Pembroke, he found a plethora of opportunities that were available to him.

“I knew I wanted to make a difference, but I wasn’t too sure how to translate that to a job,” he said.

He sat down and created goals for himself. During his first spring break in 2018, Donald went on a service trip to Tahlequah, Oklahoma to work alongside others in his program at the Cherokee National History Museum.

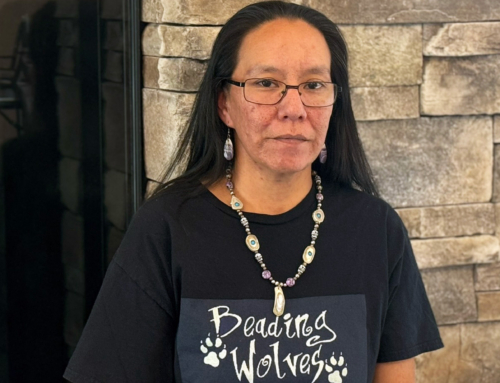

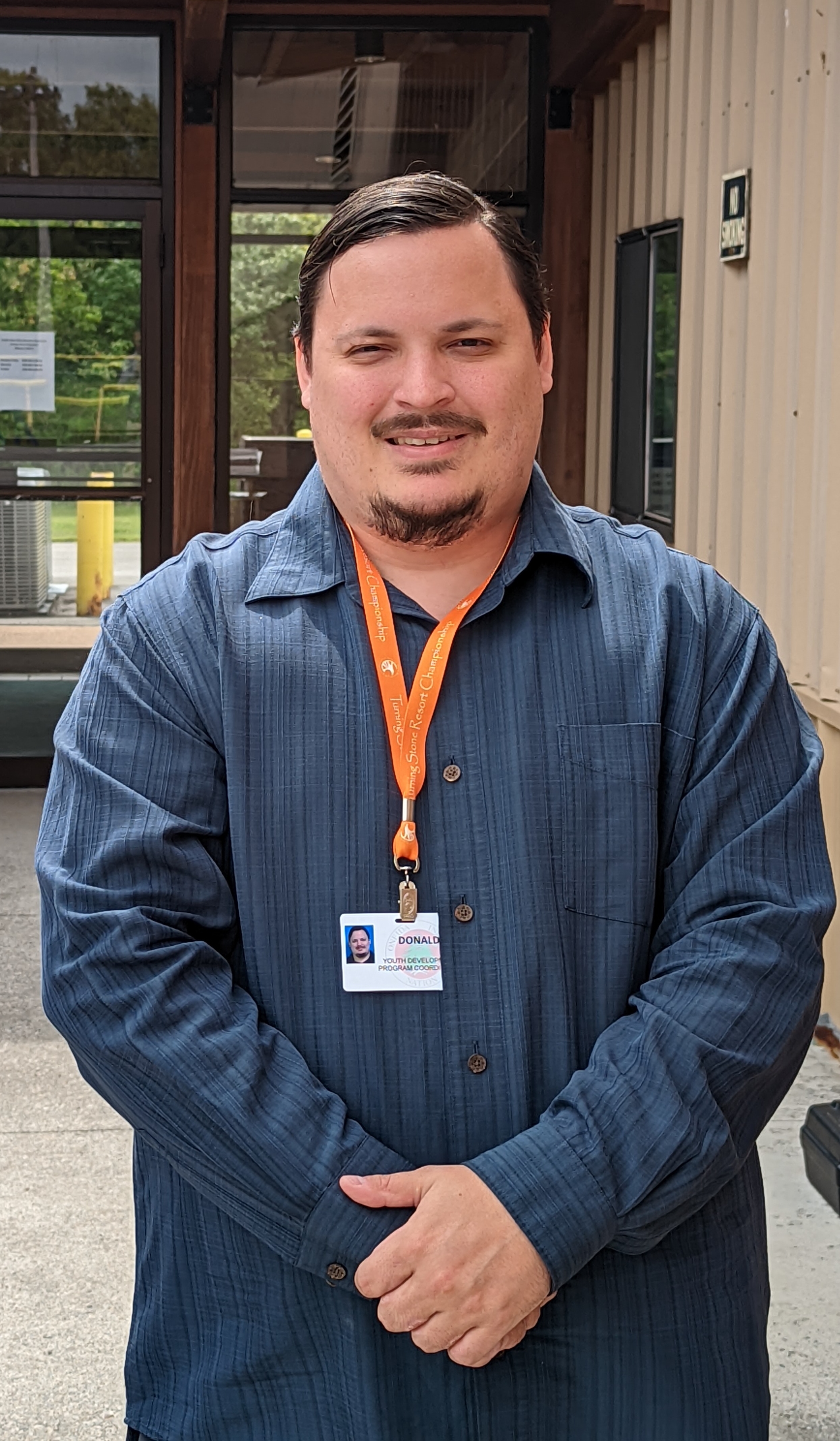

Youth Programs Coordinator Donald Gaines (Wolf Clan)

The museum was in the process of renovating the Trail of Tears indoor and outdoor exhibits. Much of the paint was dry and cracked from weather and age, so the visiting students helped out by cleaning and painting the outdoor sets. Donald was even able to learn a few words and phrases of the Cherokee language. It was a great experience that helped him get a better idea of what he wanted to get out of his education.

The following summer, he went on another service trip to Canada to network with other Native students at the University of Saskatchewan. It was after that trip that he realized what he wanted to do: become an indigenous advocate.

The two-week trip had students explore and learn firsthand from the Metis and Cree indigenous people about their culture, battles against colonization, and the modern problems they are now facing.

The group camped out on Cree lands and lived inside Cree tepees in central Canada. They also stayed with famed Metis author and activist, Maria Campbell, and visited local memorial sites and museums.

Once they returned to the university, the students split into teams to create presentations about their experiences. When answering the question of why he was on the trip, Donald thought he had a straightforward answer.

“I said I hope to work as an indigenous activist, and perhaps, in tribal government,” he said. “But I realized I never really considered what the Oneida community actually needed or wanted.”

The thought struck him like lightning. He knew he needed to become immersed in the community to determine what his best path forward would be.

“It was like a lightbulb went on in my head,” he said. “I’m telling my advisor and friends that I want to work in indigenous communities, and maybe pay it forward in my own community.”

During the next semester, though, Donald’s grandfather was killed in a car accident in Ohio. It was a life-changing moment that has stayed with him.

“I became so depressed,” he admitted. “He was such a great man and was always kind and caring.”

The shocking tragedy was especially hard on Donald’s father, Eric. But he and Donald made several trips between their home in North Carolina and Ohio to ensure Donald’s grandmother was taken care of. It took several months to muster enough motivation to attend school, and it became even more difficult to achieve academically at the level that he wanted to.

Then came the pandemic in early 2020. Suddenly, it was nearly impossible for Donald to get ahead, both mentally and academically. That’s when the Oneida Indian Nation’s former Scholarship Coordinator, Lindsey Langdon, came in and helped lift him up.

“Lindsey was a big part of getting me back on track,” Donald said. “She was so enthusiastic, compassionate and professional, which really helped me push through to finish my undergrad degree.”

After completing his degree in the spring of 2022, his first thought was to see what was open at the Oneida Indian Nation.

“Part of the reason why I wanted to come up here was to learn more about what it means to be Oneida,” he said. “If I really want to be as effective as I can be, I need to know who I am, and I felt like the youth programs coordinator position would help me connect with the community.”

Unable to embrace his heritage because of the immense obstacles that faced his ancestors, Donald always felt like he was missing something. He and his mother were proud of where they came from and grateful for the opportunities the Nation has given its Members – no matter where they lived.

It’s a reality that many Nation Members can relate to. Over the decades and centuries of cruel policies that robbed Oneidas of much of their homelands, Members were forced to move away to make ends meet. Many still faced uphill economic battles as well that led to poor mental and physical health.

“It’s always kind of weighed on her – not being able to connect to her culture,” he said. “That is why I came up here. I want to pay it forward for both of us and help enrich this community.”

Donald is excited to draw upon his mother’s experience as an elementary school teacher to make the youth programs more educational, in addition to promoting healthy habits in and out of the classroom. He knows firsthand how valuable a solid support system can be for kids.

His first assignment as the youth programs coordinator was running the popular Summer Jam program that gives kids in the community a place to go during the day to work on cultural projects and get in some physical activity.

“It was a great experience for me,” he said. “Now I can start focusing on how to make these programs even better. I’m grateful that I came here at the time that I did.”

Donald met with the Education and Recreation departments during the hiring process, which helped him get a clearer picture of the community and the Oneida Indian Nation as a whole. He said Lindsey also motivated him to explore continuing his education when he was ready to do so. Building off his educational, and now professional, experience, Donald hopes to pursue a law degree someday.

“I attended the ‘Pipeline into Law’ program to see if it’s something that might be a fit for me,” he said. “It’s a free six-week class, and it’s taught by some of the top law school recruiters, particularly those with strong American Indian law programs.”

It also has a strong alumni system, which will come in handy if he decides to go down that path. A high-ranked law school typically is able to connect students with high-quality jobs. He said working in the public sector might be another way to advance his dream of being an indigenous advocate. He hopes to attend the Pre-Law Summer Institute (PLSI) program for American Indians and Alaska Natives, which will be a great primer for law school.

But for now, Donald is happy to start his new beginning at the Nation.

“After talking with the people that worked here and being able to see their enthusiasm, I thought these are the kind of people I can work with,” he said. “I know we can make a difference.”