In 1784, Francois, Marquis de Barbé-Marbois, was a guest of the Oneidas near Fort Schuyler. The day of his arrival, he and his entourage were escorted to the Council House. They dined, and then the evening’s entertainment commenced: the Oneidas danced.

The Marquis describes the event in his book, Our Revolutionary Forefathers:

“A white flag raised on the principal cabin indicated to us the Council House…We found the chiefs and warriors of the nation assembled there. They received us with the hospitality which they show towards all those who are not their enemies. I found an old acquaintance, a venerable chief whose name is the Great Grasshopper. I had seen him in Philadelphia in 1781 … After the customary compliments; they brought us a large salmon which had just been caught. We had milk, butter, fruit and honey in abundance. We drank from goblets of wood, and M. de Lafayette, as a distinction, had one of glass mended with gum.

“We expressed a desire to see their dances, and at once one of the principal men stepped out, and blowing on a horn called the young men of the village and told them to dress for the dance, and to go without delay to the Council House to amuse the strangers. This cabin was composed of a single room twenty-four feet by eighteen. On each side were the beds on which we were to spend the night. In the middle was a sort of alley, which was the dance room. Towards each end of the central passage, there was a fire of which the smoke went out the roof… This cabin had been got ready for our reception.

“The dance began. The dancers were young men. Some dressed as warriors, others in clothes which they had received from the English…

“A warrior wears a crest of braided feathers in his hair; his face is painted with horizontal bands about an inch wide. Each band is of different color, white, red, black, blue, green, yellow, according to their fancy. They put long red or black feathers through holes which they make in their nostrils, a ring or pendants of lead or silver hang down before their mouths. They fasten bells to their arms or their feet; they wrap the body with a piece of red or black cloth; they carry a bow and arrow, and a club…They have bare thighs, and legs covered with cloth gaiters or animal skins. The leather strip over their shoulders from which a tomahawk hangs, their belt which has a dagger in it, and their traveling pouches, are embroidered. They have their hair painted red, and their ears pierced …They have modest countenances while dancing; the men leap from one foot to the other and strike the earth sharply; they [the women] dance without leaving the floor, sliding their feet. All keep time with perfect precision. When the dance had lasted two hours, we told the interpreters to ask the dancers to retire…”

But Oneidas need not look for European eyes to offer accounts of their dancing prowess. They have been dancing since time before memory and continue to embrace the tradition, passing it on to the next generation.

An ancient art, traditional dancing has been practiced on Oneida homelands throughout the centuries. News accounts chronicle the events on the Honyoust farm (Territory Road) in the 1920s. Beginning in 1924, the Iroquois Indian Primitive Industrial Exposition celebrated Haudenosaunee customs, from basketry and beadwork to lacrosse and dances. Oneida Bill Rockwell, who lived on the land, was the secretary and treasurer of the association.

According to the Oneida Dispatch from September 12, 1924, the festivities included “an exhibition of Oneida dancing, including the war, harvest and green corn dances…”

And, indeed, the September 19 Oneida Dispatch vouched for the activity that drew “more than a thousand persons, half of whom were Indians…” The article continued, stating, “…novel Redmen dances were held after the game,” an apparent reference to lacrosse.

The Oneida Democratic Union previewed the exhibition on September 27, 1927, noting that “green corn, snake and harvest dances will be presented…” A follow-up in the October 4 edition said, “More than 1,000 attended the fifth annual assembly of the Iroquois Oneidas at the Honyoust home, Oneida Reservation near Five Chimneys,” at which “dances featured the afternoon program of entertainment, given by warriors in full regalia.”

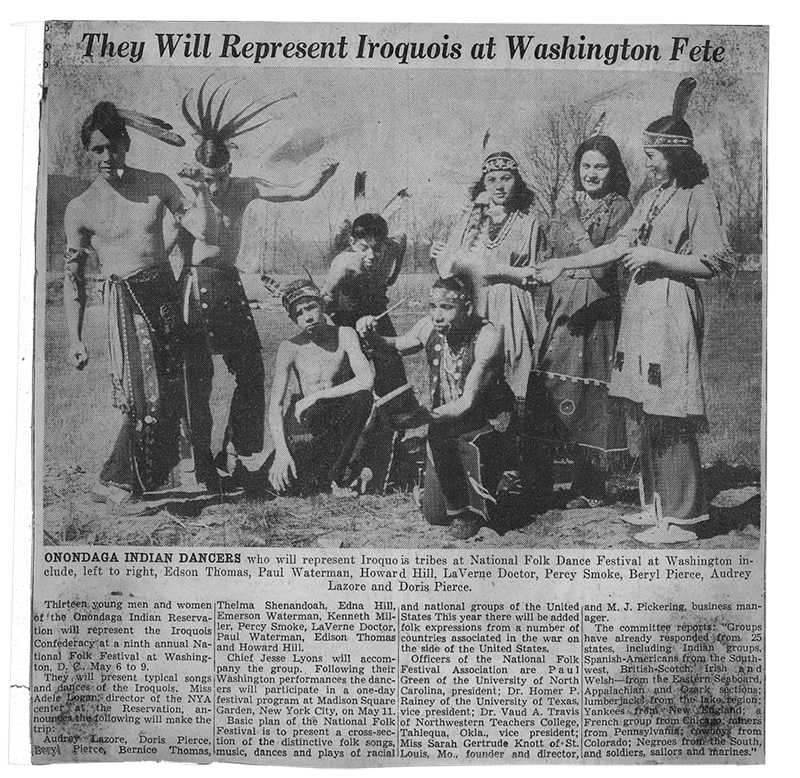

And while Oneidas on the homelands continued their dancing traditions, those who had been dispersed after the Revolutionary War (because of the loss of their villages) and settled on the Onondaga Reservation also maintained their custom. Beryl and Doris Pierce (Turtle Clan) are examples.

Pictured in a 1940s photograph from an unknown Syracuse newspaper, Beryl and Doris are shown with a group in regalia. The group was going to Washington, D.C. to represent the Haudenosaunee at the National Folk Dance Festival. From D.C., the group traveled to New York City to perform in a festival at Madison Square Garden.

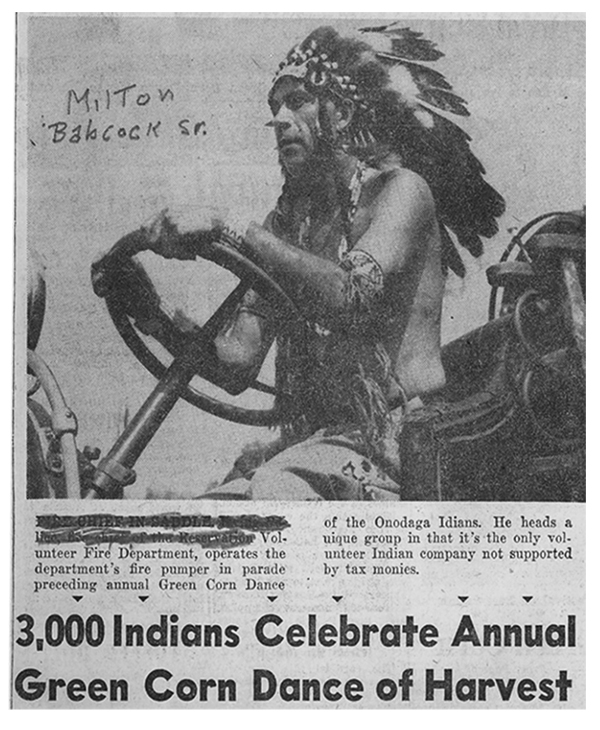

Years later, another Oneida was featured in the papers dressed in regalia. In a 1954 photo (also from an unknown Syracuse newspaper), Milton Babcock (Turtle Clan) is seen in his regalia driving the Onondaga Reservation’s Volunteer Fire Department’s fire pump in a parade that preceded a dance. The fire department sponsored the annual Green Corn Dance of the Harvest to raise funds for the volunteer group. According to the article, the festivities took place over two days.

The clip’s first paragraph reads: “The hills and valley of the Onondaga Indian Reservation yesterday again echoed … chants of two centuries ago, as 3,000 Indians celebrated their annual Green Corn Dance at the [reserve] before a crowd estimated at more than 1,000 persons.”

The Green Corn Dance was held to celebrate the yearly harvest, one of many dances enjoyed by the Haudenosaunee that also included the stomp, smoke and rabbit.

Jenna Jacobs at the 2016 New York State Fair.

Throughout the years, Oneidas also showcased their dancing abilities at the New York State Fair at the Iroquois Village. And Oneida girls – such as Sheri “Cookie” Pierce Thomas (Turtle Clan), Karen Halbritter (Wolf Clan), Kandice Watson (Wolf Clan), Daysha Honyoust Hatfield (Turtle Clan), Paullette Bucktooth (Turtle Clan), Kayla Waterman (Wolf Clan) and Jenna Jacobs (Wolf Clan) – in turn stole the spotlight as the Princess, an honor that rotates among the nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

“It was an honorable and memorable experience,” said Daysha, the 2000 Oneida Princess. “I had to lead the dancers and talk to the audience about the Nation, our clans and other cultural things. I hope my daughter is Princess someday.”

With the Oneidas’ economic renaissance, its traditions, including dance, which had been safeguarded throughout the ages, have further thrived. In 1997, the Oneida Indian Nation’s Honoring All Veterans: First American Cultural Festival was held on Nation-owned land in Canastota.

Several Oneidas competed in the dance competitions throughout the years the festival was held (the last was in 2004), including Stevie Rae Patterson (Wolf Clan), Brooke Thomas (Wolf Clan), Kayla Watson (Wolf Clan), Teyekahli:yos Edwards (Wolf Clan) and David Lyons (Turtle Clan).

Previous cultural events were held on the Nation’s 32 acres on Territory Road a half century before. The late Ray Elm (Turtle Clan) emceed the events, explaining the significance of the different dances, according to his son Lloyd.

“It was really a dance program with vendors, to raise money,” said Lloyd, who was one of the dancers. “I believe it was the first gathering of its kind in modern times on Oneida land. It was held four or five times. A lot of people attended. My dad was good at being an MC. He was the MC at the Indian Village at the New York State Fair for over 15 years.”

Dance is an expression of a culture, of a people. Like language, dance can express feelings and emotions. The Oneidas have maintained their strong connection to their traditions, including dance, through adversity and triumph and are safeguarding it for the faces yet unborn.

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2009 edition of The Oneida newsletter and has been edited.