1794 Treaty Commemorates Unique Bond Between Oneidas, U.S.

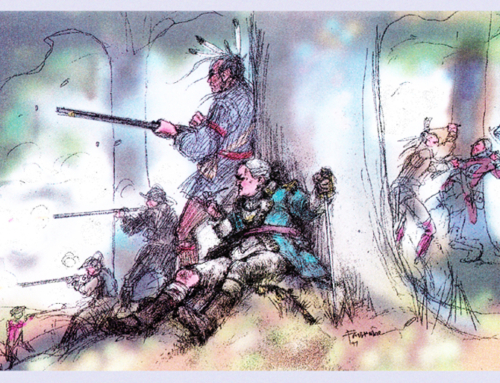

November 11 is a day of critical importance for the Oneida Indian Nation, for two reasons. It is the anniversary of the Treaty of Canandaigua, considered by many to be the United States’ oldest international treaty still in effect. It also marks the country’s official celebration of Veterans Day, a time to remember how America’s first allies have always stepped forward to help their neighbors. Since the Battle of Oriskany in 1777, Oneidas have served with honor in every armed conflict in U.S. history.

But there is more than just a history of military service to the bond between the U.S. and the Oneidas. There also is the Veterans Treaty of 1794, executed just a few weeks after the celebrated Treaty of Canandaigua, on December 2, 1794, in Oneida Castle. Created by the U.S. to document its special relationship with the Oneida Indian Nation, the Veterans Treaty recognizes the wartime sacrifices made by the Oneidas on behalf of the American people.

Timothy Pickering, special U.S. emissary to the Iroquois, negotiated the Treaty of Canandaigua, and, as soon as he was finished, he rode to Oneida Castle to conduct a second treaty, an agreement to compensate Oneidas and some Tuscaroras for losses and services in the Revolution. This pact is unique in American history. It is the only one in which the United States commemorates victory jointly achieved with an Indian ally. Indeed, it may be the only treaty in which the U.S. says “thank you” to an Indian nation.

Under the treaty, the U.S. agreed to pay the Oneidas $5,000 for their losses and services, build a gristmill and a saw mill, and provide $1,000 to rebuild a church. The treaty was ratified by Congress in January 1795, and the cash settlement was distributed among the Oneidas the following June. A sawmill was in existence by 1796. It is unclear whether the gristmill and church were ever built; the Oneidas were still seeking these facilities as late as 1805.

To arrive at the $5,000 cash payment, Pickering and his interpreters spent several days asking the Oneidas what property they had lost during the war. About 100 Oneidas were interviewed, each one giving a list of possessions to which Pickering assigned money values. Pickering’s lists show that the greatest property losses suffered by the Oneidas in the war were houses and horses.

There are two claims related to the Battle of Oriskany. One, on behalf of Hanyery, is for two blankets “lost in the battle.” The other, by Towacanoet, is for a “buck skin – taken by the Enemy in the Oriskene battle.” These statements suggest the Oneidas at Oriskany fought in traditional fashion by removing their outer garments prior to combat.

Other Oneidas aided in the defense of Fort Stanwix. Lt. Clanis Kahiktoton is commended “for extraordinary service in going express from Fort Stanwix to German Flatts [present Herkimer],” and Hanyost T,hanaghgwanegeaghu was considered “the most active in the service of the U.S. during the late war of any one single or individual Indian of the Oneida [Indian] Nation.”

The British retreated from Fort Stanwix in late August 1777 and, by late September, Oneida warriors were fighting alongside American soldiers at Saratoga. Oneidas, therefore, participated in the repulse of both British invasions from Canada, which, together, constituted the most important American victory of the Revolutionary War.

Oneidas also rendered important aid to the Continental Army at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78. The following spring, about 50 Oneida warriors arrived at Valley Forge at the request of General Washington. Immediately they joined a large scouting force commanded by Lafayette that was to investigate the British situation near Philadelphia. Against orders, Lafayette took up a fixed position at a place called Barren Hill where he was nearly surrounded by the enemy. Only timely retreat averted a major disaster for the Americans. The orderly withdrawal was made possible, in large measure, by the skirmishing of the Oneidas serving as pickets in an advanced position.

In July 1780, the Oneidas took refuge at Fort Stanwix as a large war party of pro-British Iroquois destroyed the village of Oneida Castle. For the next three years, the Oneidas were refugees, subsisting as best they could near Schenectady and Saratoga. Nevertheless, the homeless Oneidas continued to fight, participating in battles of the Mohawk Valley against large British raiding parties.

The money received by the Oneidas from the Veterans Treaty could neither buy back Oneida territory lost to New York nor motivate the federal government to make good its promise to protect the remaining Oneida lands. Still, in the Veterans Treaty, the U.S. acknowledged a special bond with the Oneida Indian Nation forged in war and joint victory – a bond that the Oneidas have honored for more than 10 generations.